By Dave Allston

Some of the lesser-known events of the summer Olympics are the shooting sports, which have been a part of the games since the first modern Olympics in Athens in 1896. One of the core shooting events is trap shooting, which has a history dating back to the 19th century. Canada has a successful history in this event, with nine gold medals at world championships.

But, did you know that in the early 20th century, one of the world’s most esteemed gun clubs and trap shooting facilities was located in rural Westboro?

There are many interesting pieces to Westboro’s early days that emerge the deeper one digs into old records. One such discovery was the story of the St. Hubert’s Gun Club, which called Westboro home for over 30 years.

A century ago, when Westboro was still in the midst of converting from farmland to residential neighbourhood, there were large pockets of former farmland that sat vacant, waiting for inevitable development.

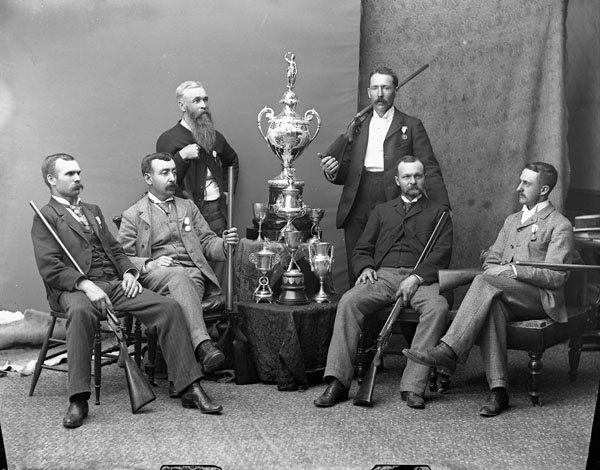

Meanwhile, St. Hubert’s Gun Club had called the Dominion Rifle Range—located on today’s Strathcona Park—home since its creation in 1884. It also occasionally used the facilities at the Rockcliffe Rifle Range as well. The club had achieved an astonishing amount of success in both national and international competition, boasting some of the top individual and team shooters in the world.

By 1901, the club wanted its own space, accessible by streetcar during winter and summer (which its other locations were not). One of the club’s board members offered a prime location: rural Westboro, alongside the year old streetcar line. Fred A. Heney owned much of the land between Carling and Scott Street, in the vicinity of Hilson and Kirkwood Avenues. His mansion, which stood on the site of the Canadian Bank Note Company, overlooked a great farm that, by 1901, was beginning the transition to residential. He gave the club free use of a sizable piece of his property, just south of Byron Avenue.

The present-day houses of Dawson and Bevan Avenues sit on top of the original St. Hubert’s Gun Club property. The noisy weekend competitions of a century ago are hardly imaginable in this quiet section of Westboro.

In the middle of today’s Wesley Avenue, just a little west of Dawson, stood the gun club’s clubhouse—a relic house that had stood in seclusion well back from Richmond Road, in the true wilderness of 19th century Nepean Township. The house had been owned and possibly built by famed architect Thomas Stent, who acquired the property in 1861 while two of the many buildings he designed—the East and West Blocks of Parliament Hill—were under construction. He moved to New York City a few years later, leaving his motivations for owning that property and house to the pages of history. It was later owned for 25 years by William E. Hayes before being transferred back to the Heney family.

The move to Westboro was a major upgrade for the club into what were referred to as “substantial quarters and grounds up-to-date in improvement and equipment.”

On Saturday, May 4, 1901, the first competition at Westboro was held, with Col. John Tilton—former Commander of the Governor General’s Foot Guard—firing the first shot at the new club. The first competition included 20 birds (10 known and 10 unknown angles), with A.W. Throop of Nepean Street winning the silver spoon, hitting 15 (Heney hit 11).

Each week, the club would hold competitions with matches such as these called “spoons,” as well as “sweeps” of five, 10 or 15 shots. Competitions were held almost exclusively on Saturday afternoons (though there were reports of the occasional weekday afternoon match) and would be held year round. Only hunting season in the fall would temporarily cease club activities.

Wind was a big concern, and, out on the rather flat fields of Westboro, it could alter a competition.

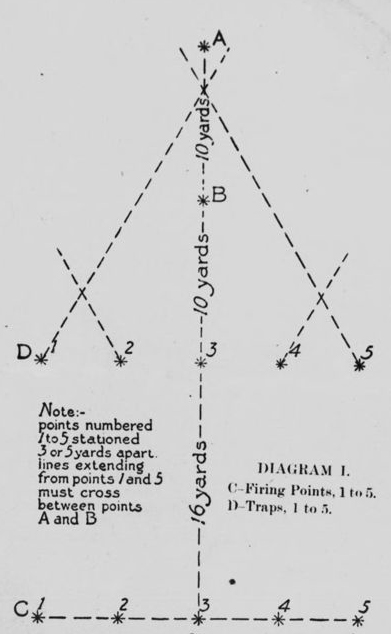

At the Westboro grounds, the traps were arranged differently than most clubs.

“Instead of having a somewhat high board screen in front, they will be located in a pit just behind a little sodded mound,” reported the Ottawa Journal.

Three systems of traps were installed: the Sergeant or three-trap system; the ordinary five-trap system; and the Magautrap system by which the clay birds were discharged from practically the same trap but at unknown angles. There was an area where shooters would stand three to five yards apart in a line and 16 yards back from the traps. The five traps would similarly be arranged three to five yards apart in a line, and were powered to fire a clay pigeon 40 to 60 yards, with a flight six to 12 feet high, 10 yards from the traps.

In the earliest days, real live pigeons were actually used. In fact, at the 1900 Olympics in Paris, live pigeon shooting was a medalled event. In Ottawa, the St. Hubert’s Club had used live birds during the 1800s. In 1886, the club was the focus of a case by the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, who witnessed mistreatment of the pigeons, both prior to and during a tournament that July. The case was dismissed, as it was found that the shooter’s intention was to kill the bird. If he only injured the pigeon, it was an accident. It was just two weeks prior to the opening of the Westboro club that the U.S. Senate banned the shooting of live pigeons as “cruel, merciless and unnecessary sport.”

Even further back, the original traps were containers which held the live birds. The original traps used were top hats. The birds were placed under the hat, and a string attached to the hat. A command of “pull” was given to pull the string, releasing the bird. Hence, how the term “pull” is still used today.

The St. Hubert’s Club, meanwhile, had a long history dating back to February 1884, when it became the first organized trap shooting club in Canada. Founded by Jean-Charles Taché, the club originally was open to French-Canadians only.

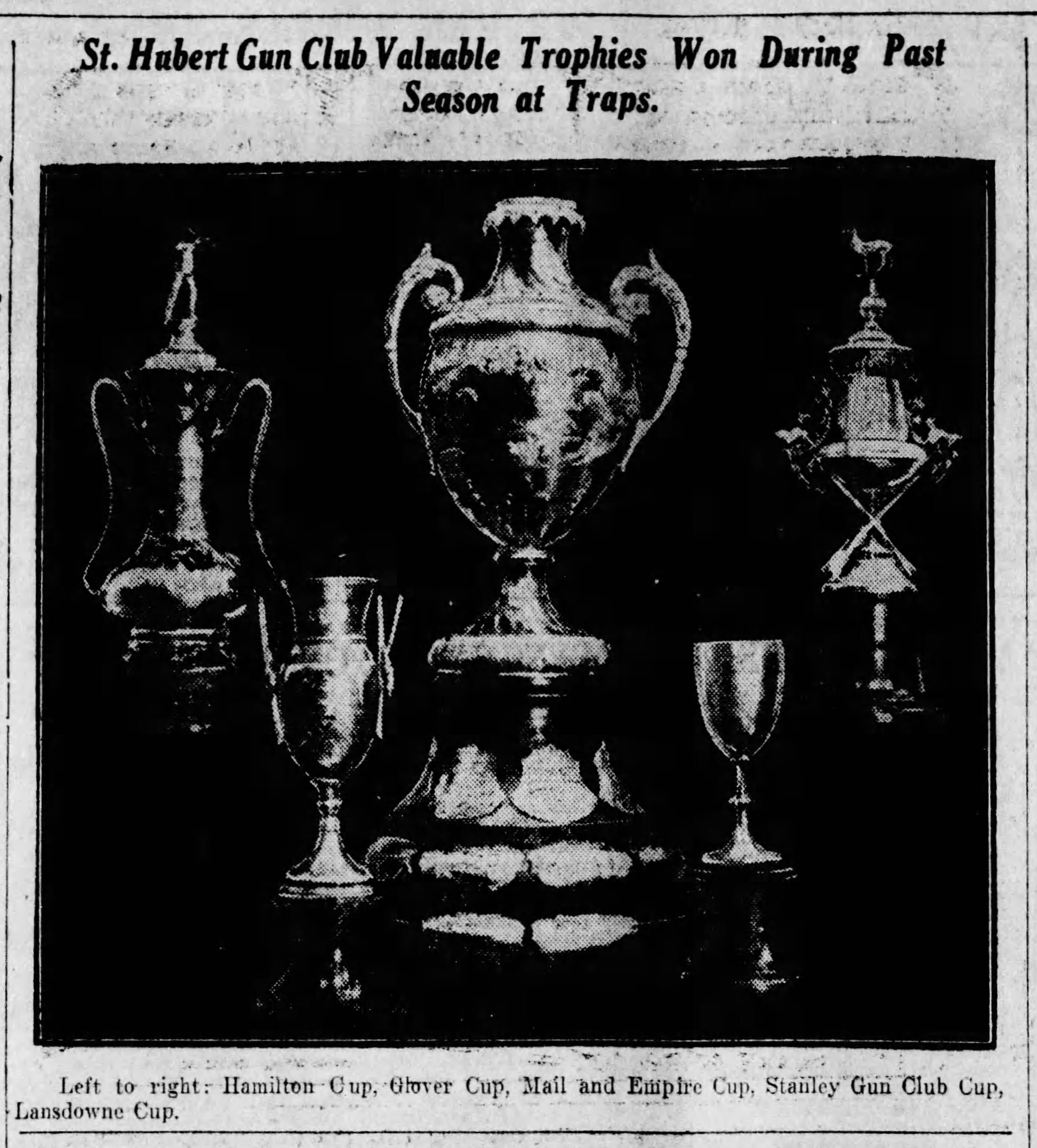

The club became the showcase organization in Canada, winning early major trophies such as the Lansdowne Trophy (given by Governor-General Lord Lansdowne), the Stanley Cup and the Mail Trophy. Later local trophies such as the Birks Cup and Bedard Deerhead trophy were sought after, and in 1919, hockey superstar Art Ross donated a trophy in his name to the club (though his tie-in to St. Hubert’s is a mystery).

Several prominent local citizens became members of the club, including, notably, Zeb Ketchum, who operated the Ketchum Manufacturing plant on Richmond Road.

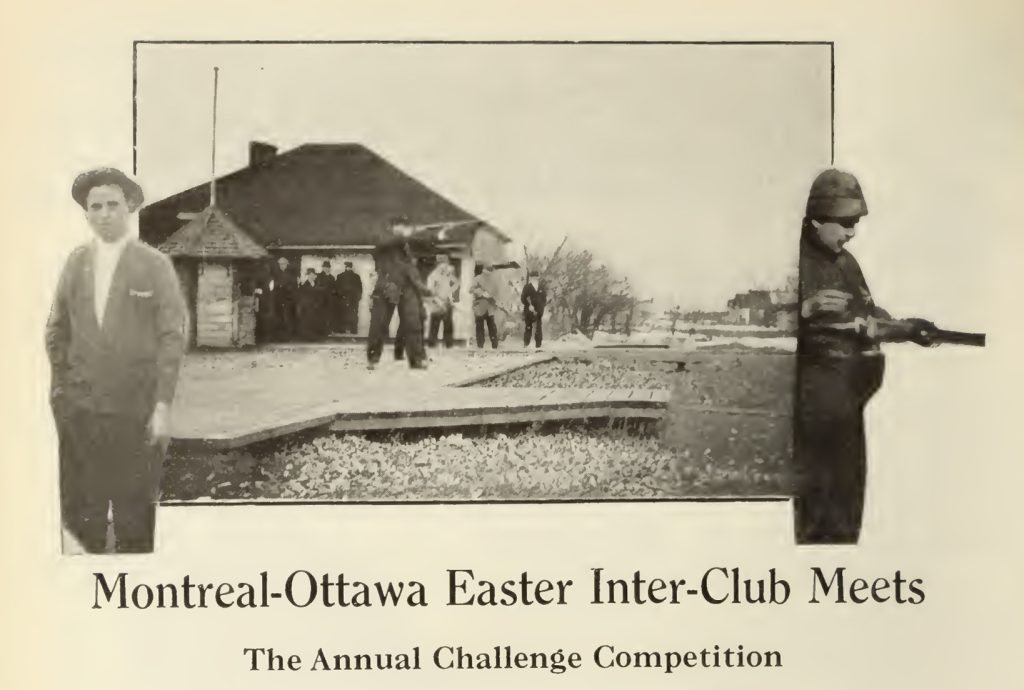

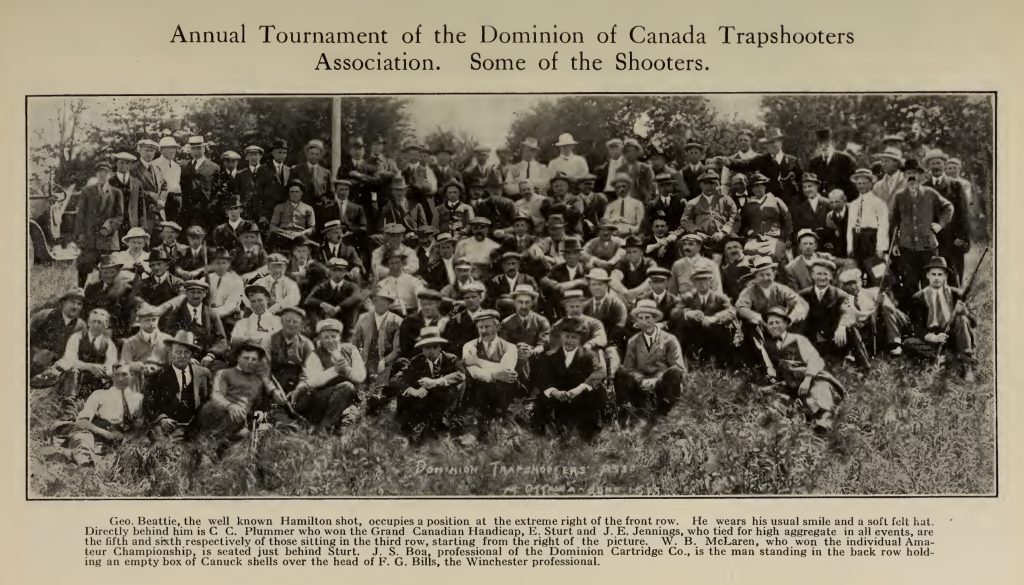

It was primarily through St. Hubert’s efforts which led to the establishment of a Dominion Trap Shooting Association in 1901.

From 1901-1920, St. Hubert’s operated out of this location in Westboro while the neighbourhood around it began to grow. The area became busy, and a large grove of trees proved to be a continually frustrating background for the shooters, who required an unobstructed view. As well, following WWI, the club had a surge in popularity.

“Now that Canadians in general are quiet on the Western Front, and let us hope permanently so, red-blooded he-men through the length and breadth of the land are burning powder in a manner strikingly in contrast to that which was in vogue ‘over there’ during the season of 1914-1918, the mode of procedure being much more conductive of longevity to the human race,” wrote the Ottawa Citizen in April 1920.

Thus, for several years, St. Hubert’s moved locations, at first moving to the river’s edge at New Orchard Beach near Woodroffe, later to Sussex Street downtown. Finally, in April 1930, the club opened a new clubhouse and grounds on Carling Avenue, just west of Broadview Avenue on John E. Cole’s property.

The 12-acre plot of land featured a new clubhouse (located about where S&G Fries stands today) and an impressive new field, upon which were built three traps, each having five shooting positions. The club still included several locals at that time, including local builder David Younghusband.

For nine years, the club ran their shoots on Carling Avenue, but ceased operations in 1939, likely due to a combination of the Great Depression and WWII, as well as a general decline in the popularity of trap shooting.

Fifty-five years of the prestigious St. Hubert’s Gun Club (over 30 of them in the west end) had come to an end, and more than 80 years later, their story is just one piece of the vast, lost history of early Kitchissippi.