By Dave Allston –

History fever has hit Wellington Village this summer as the neighbourhood celebrates its 100th –but a big chunk of the area’s history has yet to be told.

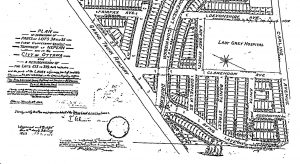

Though today the neighbourhood runs north from the Queensway with streets laid out mostly alphabetically from Edina to Kenora, original plans called for another half of the subdivision to the south–a potentially huge community that never came to fruition.

The story begins back in March 1909, when a site for Ottawa’s badly needed tuberculosis hospital was finally selected after a year-long debate. Five acres of the Ottawa Land Association’s vacant property on Carling Avenue in the distant suburbs were sold to the City of Ottawa for $7,500, and on this site the new Lady Grey Hospital was built. (The property is now home to the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre.)

Initial plans called for the hospital to be built in Hintonburg on the south side of Gladstone Avenue at Bayswater Avenue, and a myriad of other locations were debated (including a site on Hilson Avenue and another near Richmond Road at Woodroffe Avenue) before the Carling location was selected.

In retrospect, it was an odd choice. The location was ideal due to its isolation from populated areas, but the cost of acquiring the land and the need to extend water services a long distance, not to mention build sewage systems, made it an expensive proposition.

The Lady Grey Hospital opened on Feb. 16, 1910 as a “sanatorium” for citizens suffering from advanced cases of the “Great White Plague.” It was built on a hill, screened in by a grove of hardwood trees, with many windows and large verandahs to maximize fresh air, one of the primary treatments for TB. The hospital had space for between 42 and 46 patients.

Meanwhile, by 1913, the OLA was finally taking steps to begin selling off its hundreds of suburban acres of increasingly prime land. World War I would curtail those plans for a few years, but early unregistered plans laid out the new subdivision, which included many new streets from Carling all the way to Scott Street, fitting into surrounding neighbourhoods like pieces of a puzzle.

Streets such as Iona, Java and Kenora are of course well-known today. Keen observers have noted that they appear almost in alphabetic sequence–except for Faraday, which oddly is out of order. This is explained by the fact that Faraday was originally a street in the Hintonburg plan of 1895 to the east (in May 1941, that original segment of Faraday east of Holland was renamed Sherwood Drive to eliminate confusion for delivery drivers and postal workers).

The OLA decided to extend Faraday (as well as Ruskin) to the west and add the new streets around it in alphabetical order from south to north, even though Faraday broke the pattern. Today, the sequence of streets begins at the Queensway with Edina, but the original subdivision started with the letter A and included streets called Anita, Bonita, Cornelia, Diana, Edina, Formosa, Geneva, Helena, Iona, Java and Kenora. The north-south streets still exist today but were originally longer (Clarendon ran all the way to Carling, for example).

The OLA selected the names for the streets randomly; there were no connections to the families of the OLA Directors, nor were the names pertinent to the Stewart family, who farmed the land in the 19th century.

Island Park Drive was laid out by the National Capital Commission’s forerunner, the Ottawa Improvement Commission, between 1921 and 1923 and opened for traffic in the fall of 1923. The location of the Lady Grey Hospital likely influenced the street’s route, as it looped sharply around the edge of the hospital property.

When the official subdivision plan was finally registered in 1923, it included a few key tweaks to account for Island Park Drive, as well as a few other changes from the original design (Formosa Street was lost entirely, rear lanes were added for all streets and Island Park Drive branched in two directions where it met Diana Street just over the tracks).

The southern half of the subdivision was divided by the Grand Trunk Railway tracks, which ran the same route that the Queensway does today. This divide would drive the next series of developments.

opular with homebuyers, and the OLA began taking steps to establish infrastructure. The city began installing a sewer network in part of the new neighbourhood west of the Lady Grey (on Anita, Bonita and Cornelia streets). Aerial photos from the mid- to late 1920s capture the altered ground, which had previously been untouched farm land, clearly showing the lines where sewers had been laid (streets still existed only on paper at this point).

For whatever reason, the OLA never sold any of the lots in this subdivision, and other than a group of 10 chicken coops on Bonita Avenue, the area was never developed.

In June 1928, the Ottawa Hydro Electric Commission acquired many of these lots bordering Carling, and in 1929 it opened No. 3 substation to alleviate Ottawa’s reliance on electricity from the Gatineau Power Company. The substation and related infrastructure, as well as the Roberts/Smart Centre and Youth Services Bureau at the west end of the Royal property today, stand above where the 1923-24 unused sewers likely still lie beneath.

By 1937, in the midst of the seemingly never-ending Great Depression,

the OLA was looking to sell off its remaining holdings and close out the syndicate after nearly 50 years of existence. The city acquired much of the land surrounding the hospital for just over $22,000, later granting most of it to the Royal Ottawa for expansion and adding the infamous water tower in 1950. Thus, much of the originally planned residential community south of the Queensway would never materialize.

Who knows what could have been had city officials chosen to open the tuberculosis hospital on Bayswater (or any of the other 20-plus sites considered)? It’s likely the area south of what is now the Queensway would have been built up as residential, and some of the most desirable streets in Kitchissippi today might be Anita, Bonita and Cornelia!

Dave Allston is a local historian and author of The Kitchissippi Museum (kitchissippimuseum.blogspot.ca). His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have early memories or photos to share? Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.