For decades Aylmer island has been a hangout spot for families, kayakers, and party-goer teens. Over the generations, stories have been passed down about ancient Indian bones buried at the site.

When Rick Henderson was only a little kid, he discovered the urban legends were true.

“I was an eight-year-old boy. My father was an avid boater and he knew a lot about the history of the area,” Henderson recalled to KT. “It was only a rumor that Alymer island was an ancient burial ground until one summer day when his friend Pierre Normandin led us in his boat and he was going to show us where the bones were. It was fascinating.”

Henderson said Normandin, a local CBC producer, had been to the island before and reburied the bones he previously discovered.

How the bones got there and how old they are remains a mystery. Some experts state they could be upwards of 4,000 years old. The long forgotten story was unearthed for the first time in over a century last month when historian Andrew King, a former Westboro resident, wrote about it on his blog at ottawarewind.com.

The first discovery

Knowledge of bones being on the island was first published in the late 1890s by Thomas Walter Edwin Sowter, who, according to the Canadian Museum of History, was the Ottawa Valley’s first archaeologist.

His discovery of the human remains came as a result of the Alymer lighthouse construction in 1883. The island is about an acre in size and is situated about a kilometer from the Ottawa shoreline.

“I have assisted at the exhumation of several skeletons, which has given me a fairly accurate insight into the mode of sepulture which obtained among the aboriginal people of Lake Deschênes,” Sowter wrote. “There is abundant evidence to show that the island has been used as a burial place from very early times down to a period so comparatively recent as to come within the memory of those of the generation that is now passing away.”

According to the archeologist’s report, a wagon full of bones and artifacts were discovered in various places around the island. Among the peculiar finds was the skeleton of an individual found buried in a reclined seated position. Further examinations determined the individual was killed by an arrow that entered his lower back.

Sowter said the burials were strange as they did not align with known Indigenous practices and rituals in the area. Most Indigenous bodies were buried in a prostrate position, he said.

According to King’s reporting, the remains might be from the Huron people. They had an ancient tradition called “the feast of the dead.” The Wyandot people, as they were called, resided in central Ontario.

“The custom of burying their dead involved the disinterment of deceased relatives from their initial individual graves followed by their reburial in a final communal grave,” wrote King. “This ritual was both for mourning and celebration, and was documented by the Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf who was invited in the spring of 1636 to a large Feast of the Dead on a beach near Midland, Ontario.”

It was common for reburials to take place every 10 years or so, with the bones sometimes being transported far away from their original resting places.

What’s not understood, however, is why the Huron would be on Alymer Island when there is no documented proof of their people residing near the Ottawa River.

Sowter speculated the Huron may have been given sanctuary by the Algonquin First Nations after they were defeated in other regions.

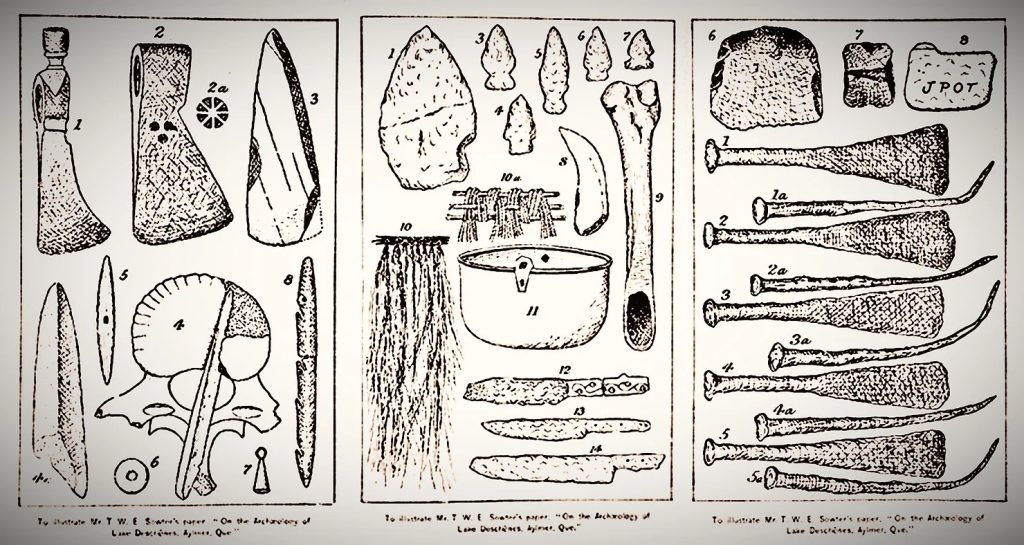

A two pound iron axe, a knife with an intricate inlaid copper vine motif on its handle, a bone harpoon, a copper kettle with an iron handle, and human hair wrapped in birch bark were also unearthed for the first time in centuries. A Toronto archeologist by the name of David Boyle said the items were of European descent.

There was also a stone slab with “JPOT” inscribed into it, which was perhaps a grave marker.

Honouring the dead

It’s unclear what has happened to the bones and artifacts taken off the island, but at least some remain there today. Henderson said he’s heard of a few people who unintentionally came across them over the years.

“Four years ago, a friend’s 14-year-old son and his friends were there for his birthday party. They came upon several bones. She was pretty well aware that they were likely ancient, but she didn’t know what to do so she called me,” he said. “She called the OPP and I took charge of notifying the two reserves — the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Cultural Centre and the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan Council.”

Police confirmed the bones were old, and said it was up to the Indigenous communities over how to proceed. To date, no action has been taken.

Verna McGregor, an elder and cultural spokesperson in the Algonquin community, said she’d like to see the site be protected.

“The bones have just been disregarded; they were there for a reason. There were probably artifacts with the remains too, and sometimes they get picked over and that’s very disrespectful,” McGregor told KT. “I think there still needs to be a full consultation process over what happens when something of major historical significance happens at a place like Aylmer Island. Like everybody else’s remains, we’d like to have them protected.”

McGregor said the island is a sacred place that can be used to teach future generations about the racism and misrepresentation Indigenous people have faced in Canada for centuries.

“We were known as the river people. Our method of travel was the birch bark canoe. It was common practice to bury our ancestors along the Ottawa river,” she said. “It would be a good idea to gather people out of respect, but also for reconnection to our lands.”

Despite its name, Alymer island is actually located in Bay ward on the Ottawa side of the river. Area councillor Theresa Kavanagh, an avid kayaker who has taken day trips to the site, said she was shocked to read about what’s hidden below the layers of sand and dirt.

Kavanagh said she has plans to connect with the local Indigenous communities to see what kind of memorial can be erected.

“I was blown away. We need to treat it seriously and protect the island. It looks like a lot of partying goes on there and it needs some tender loving care,” said Kavanagh. “But we need to talk to First Nations about that. They need to have a say on what the next steps would be.”