This year marks the 100th anniversary of prohibition in Ontario, a significant era in the perennial saga of liquor and its control. Prohibition did not happen suddenly; it was the result of a long-running temperance movement culminating with evolving social and economic factors of the time and most importantly, the onset of World War I.

The temperance push was long fought by well-intentioned individuals who believed a better society could be achieved. The first temperance society in Upper Canada was formed in 1828, and legislation in 1865 and 1878 empowered municipalities to ban alcohol locally. The first national referendum on prohibition was held in 1898, and passed with 51%. The Laurier government did not feel the voter turnout (44%) was strong enough to merit changing the law but it was evident that the mood towards alcohol was changing.

Alcohol played an important role in the early days of Kitchissippi. Throughout the 19th century, liquor purveyors operated out of log farmhouses, general stores, and small inns and taverns which catered to farmers and travellers. The licensing of these sellers was managed by provincial commissioners.

In 1820, ten of Nepean Township’s first 40 pioneer families operated taverns, along Richmond Road.

In Kitchissippi, the first tavern was opened by Joseph McGaw in 1864 in his rustic wood-frame home on Wellington near Carruthers (where the OWCS now stands). The next one opened in William Taylor’s new hotel at the south-east corner of Parkdale Avenue in 1868.

In Westboro, Joseph Birch opened a hotel on the north-east corner of Richmond and Churchill in 1873.

Mechanicsville’s tavern was operated by Hyacinthe Latreille, who ran a hotel and grocery store on Hinchey. Latreille was licensed from 1889 until selling to Jean Bte. Rousson in 1901, who kept the hotel going until 1908.

While prohibition was not legislated until 1916, alcohol’s presence was diminishing. The number of licenses issued fell (Ontario had 4,794 taverns in 1875, only 1,371 by 1914), and the number of municipalities voting for local prohibition were increasing (by 1916, 575 of 851 were dry). This included Nepean Township, who narrowly met the 60% requirement (by one vote) for local option in 1907, forcing the closure of the classic Richmond Road taverns (Westboro voted 126-43 for local option, Mechanicsville 85-20 against).

The Ontario government legislated prohibition without a public vote through the Ontario Temperance Act (OTA), which took effect September 16, 1916. It was seen as necessary to Canada’s success in the war. All bars and liquor shops were closed for the duration of the war. No person could sell liquor without government authorization, nor could liquor be kept, given or consumed anywhere except in a private home. It could only be sold for sacramental, industrial, artistic, mechanical, scientific or medicinal purposes. Production of alcohol could continue, but all sales had to be outside of Ontario. Heavy fines were established for those breaking the law.

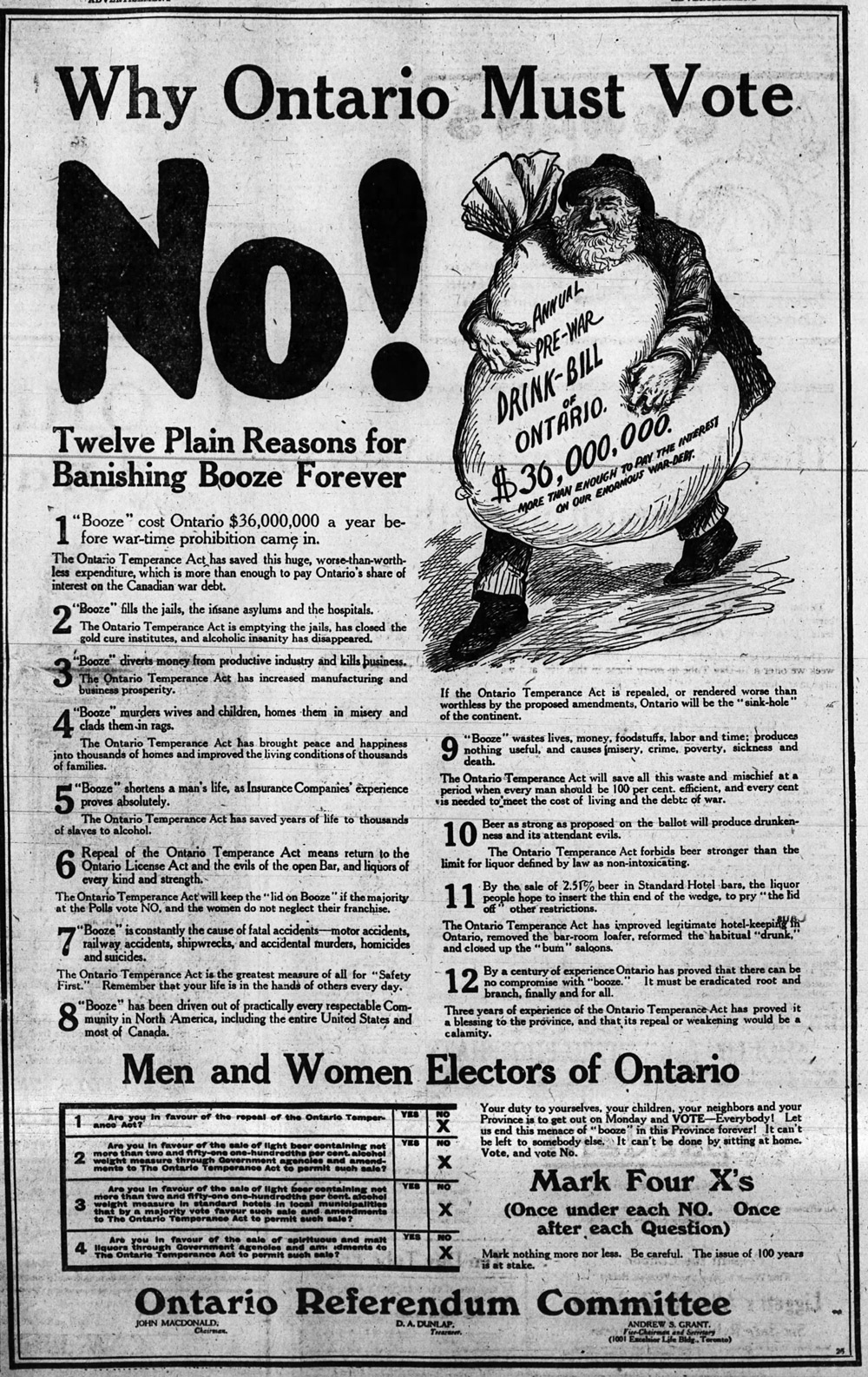

In October 1919, Ontarians were given a referendum to decide whether the OTA should be continued during peacetime. It was wildly contentious.

Maclean’s magazine summarized the issue best: “Did somebody slip something over on us while the casualty lists blinded our eyes with tears…Did we give up drink because giving up things was the fashion – horse races, baseball, banquets, time, money – all as nothing compared with the lives our boys gave up on the battle field? Did we give it up because it was the easiest, safest, long-distance way of martyrizing ourselves – of suffering something for the war which implied personal discomfort? Why did we give it up? And when we gave it up did we mean it?”

Those who supported prohibition argued that it improved home life, led to better education, improved public health and safety, increased the regularity, punctuality and efficiency of workers, improved commerce, reduced crime and resulted in a moral community. Those against argued for the democratic traditions of personal liberty, and less interference by the state.

The Globe editorialized: “Booze fills the jails, the insane asylums and the hospitals. It diverts money from productive industry and kills business, murders wives and children, and homes them in misery. By a century of experience Ontario has proved that there can be no compromise with booze. It must be eradicated root and branch, finally and for all.”

Across Ontario, 68% of electors voted to maintain prohibition. Ottawa was 53% in favour. The two sides of Wellington Street in Hintonburg had vastly different opinions: north of Wellington residents voted 686 -386 to get rid of prohibition; south of Wellington they voted 1064-718 to keep it.

Prohibition proved successful for many reasons: women, first enfranchised in Ontario in 1917, were nearly unanimous in their push; temperance leaders were well organized and politically strong; most churches were spiritedly supportive; promotion was extensive; the emotions of WWI were still vivid; the US and other neighbours were already going dry (proponents argued that Ontario would become the “saloon of the continent” and the “beer-garden of America” if it remained wet), and generally, disapproval and prohibition was de rigueur for the era.

Ontario residents could still acquire alcohol by prescription. In 1920, Ontario doctors wrote more than 650,000 such prescriptions. Other ways to obtain it included home brewing, private social clubs, secret “blind pigs” and speakeasies, or the local neighbourhood bootlegger, for whom avoiding police detection was part of the game. One bootlegger was known to run his supply over the Champlain Bridge in the back of a hearse. Another, who lived on Ladouceur Street, survived raids by keeping his product and records under the floorboards of his stable, upon which stood a 1800 lb., mean-tempered Percheron horse. Only the owner was able to move the horse out of the way.

In 1924, a new referendum was held, asking to maintain prohibition or allow sales through government control. Provincially, 52% voted to keep prohibition, but in Ottawa, 63% voted to allow government control. Individual neighbourhood opinions varied: McKellar (71-19 for prohibition), Highland Park (125-48 for), Westboro (563-515 for), Hampton-Hilson (170-93 against), Wellington Village north of Wellington (150-108 against), Wellington Village south of Wellington (151-125 for), Mechanicsville (360-37 against), Hintonburg north of Wellington (973-290 against), and Hintonburg south of Wellington (1000-932 against).

In the 1926 provincial election, the Conservatives won on a platform to re-introduce the sale of liquor. Public opinion had softened and the government had become increasingly unable to control illegal consumption and importation.

The Liquor Control Act of 1927 brought an end to prohibition, and established the LCBO, which allowed the government to manage stores and distribution. Kitchissippi’s first LCBO opened in May 1929 at 1008 Wellington (now the Wellington Eatery) where it remained until 1978.

In 1934, the LCBO allowed by-the-glass sale of alcohol in hotels and taverns. The Elmdale Hotel was one of the first to take advantage of this renewed freedom.

From 1927 to 1962, the LCBO required citizens to apply for permits in order to make a purchase. Permits had to be presented at point of purchase. If a clerk felt the buyer had exceeded a reasonable quantity for the week, the sale could be denied.

Nepean Township was one of last to repeal the ban in 1965. Until annexation to Ottawa in 1950, Westboro remained dry.

Dave Allston is a local history buff who researches and writes house histories and publishes a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have early memories to share? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.