To many, the Sir John A. MacDonald Parkway along the Ottawa River is a simple, convenient and scenic way to move around town. However, the history behind it is so much more complex. Many view its construction as the turning point in the history of many of Kitchissippi’s neighbourhoods, and not necessarily for the best. It took exceptionally long to build, came with a high price tag, forced the relocation of many families and isolated the waterfront, around which much of the old west end was built.

In 1946, the Federal District Commission (which would soon change its name to National Capital Commission) began work on a master plan for the National Capital Region. Prime Minister Mackenzie King had met renowned French planner, Jacques Gréber, in Paris prior to WWII and recruited him to develop a vision for the future of Ottawa. Roads and parkways were Gréber’s key focus, embracing the automobile as the future, in lieu of railways. Though his plan was not finalized until 1950, Gréber’s recommendations were acted upon as early as 1947.

It was on July 26, 1947 that the FDC announced that expropriation papers had been filed to force the transfer of ownership of all the properties along the Ottawa River from LeBreton Flats to McKellar Park (as well as those along the south bank of the Rideau River from Overbrook to Mooney’s Bay). The news had been kept a secret to prevent an artificial land-value boom. Owners of houses and cottages along the River woke up to the news that their homes were no longer theirs.

Expropriation left no recourse for property owners. All they could do was negotiate the sale price, which they would do individually with the FDC (when an agreement could not be reached, the Exchequer Court would arbitrate). Most were allowed to remain on their property until actual development began, becoming tenants of the FDC, and suddenly paying rent on the homes they had owned.

Communities such as Champlain Park, Westboro and Woodroffe owed their early existence to the waterfront. All had started out as cottage communities along the streetcar line, developing into busy and proud communities whose residents’ lives revolved around the river. Now a large percentage of the population would be forced to move and the river would be tucked away from the remainder of the neighbourhood. The FDC felt they were appeasing residents with the promises of building recreation centres and bathing beaches, but this was far from satisfactory to the thousands of displaced residents, many of whom knew only of life down by the riverside.

As far back as the Holt Commission report in 1915, the acquisition of riverfront land by the FDC was recommended as a must, before land values reached unaffordable rates. The depression, WWII, and the general housing shortage of the mid-40s delayed the action, but it was inevitable.

Editorials supported the move, referring to it as “safeguarding the future” and “saving for the people the river frontage upon which rests so much of the charm of the Ottawa area.” Ottawa Mayor Stanley Lewis stated, “without such action, the planning of the National Capital area would be gravely handicapped.” With a large portion of the proposed Ottawa River Parkway falling in Nepean Township, the new parkway also sealed the deal for annexation, which came in 1950.

The Parkway project was riddled with delays and took 20 years to build. In the end, the NCC opened only a fraction of the roadway and on/off points that had been originally envisioned.

By 1959, almost all of the land had been expropriated, and the houses moved or demolished. In 12 years, the NCC spent $10M acquiring 4,000 acres of land for 45 miles of the parkway to be built.

[Click photos to enlarge and view caption text. Story continues below.]

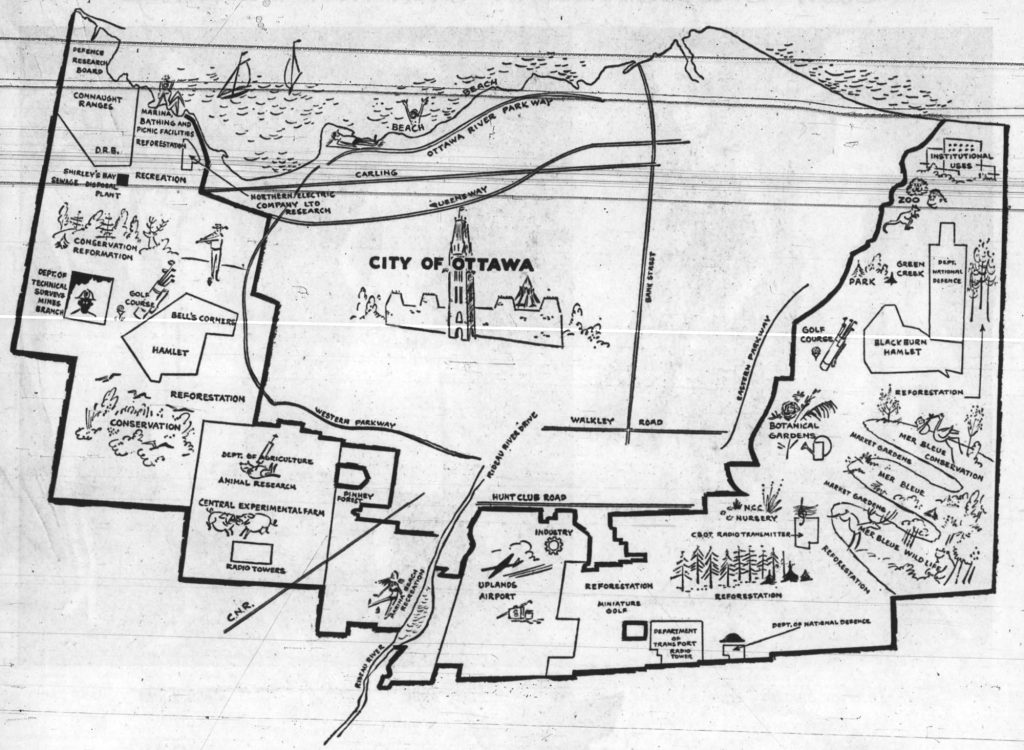

Ottawa was full of major projects being led by the NCC at this time: the railway system was being relocated to the southern and eastern edges of the city; the Green Belt was being established; the Queensway built; Tunney’s Pasture was growing while LeBreton Flats was razed. The NCC even had wild plans for botanical gardens, a zoo, bird sanctuaries, golf courses, and a major sports stadium and arena. It was a city in transition. Sound familiar?

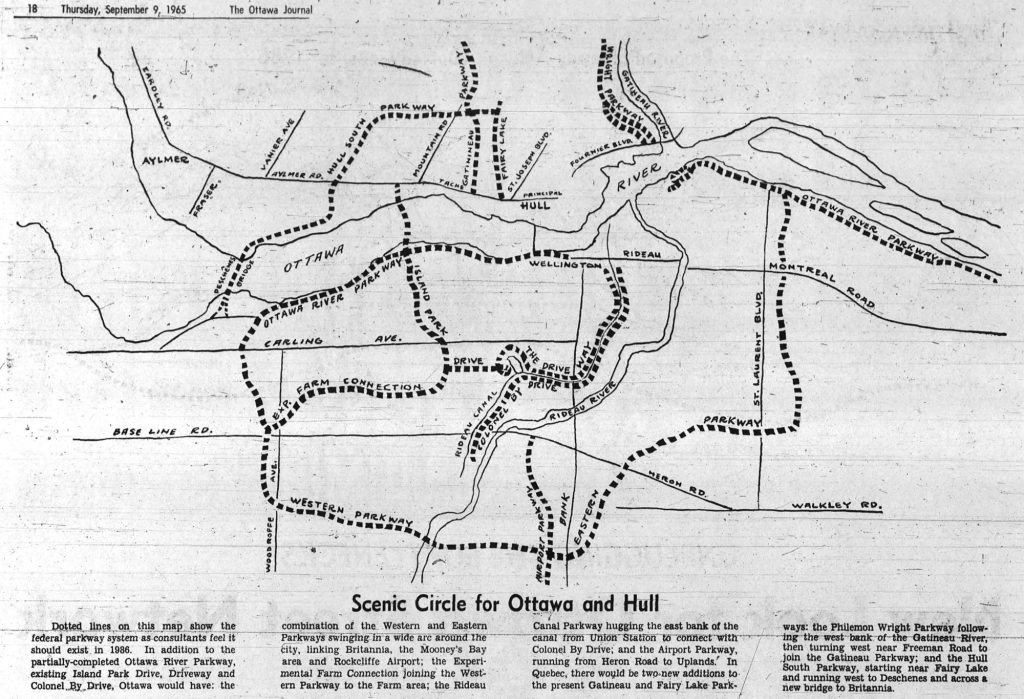

The original design of the Parkway had it extending to Britannia, where it would connect to a bridge to Gatineau, and then loop south to a Western Parkway (following the route of today’s Transitway) that would connect with an Eastern Parkway, creating a full ring around the city. Of course this was never built.

Even the SJAM Parkway design was modified over time. There were beaches planned for Champlain Park, Woodroffe and New Orchard (as well as Westboro and Britannia). The overpasses at Carleton Avenue were built to access the Champlain Park beach, which was to be an equal to Westboro’s, a “pride-of-the-city beach” that was later abandoned. (The parking lot at Remic Rapids was created for this purpose.)

Planned access points also changed over the years, with exits nearly existing at Rochester Field and at Sherbourne next to Unitarian House (which was to replace the Woodroffe exit). Churchill was an access road before it was closed. Island Park Drive was initially supposed to be an overpass.

The SJAM Parkway was constructed in three phases. The first phase, which opened on December 17, 1963, ran from Parkdale to Churchill. The second phase extended the Parkway west to Woodroffe, opening a year later on December 23, 1964. The final phase, which was the most difficult, opened on July 7, 1967, extending the Parkway to Carling on the west, and Wellington on the east.

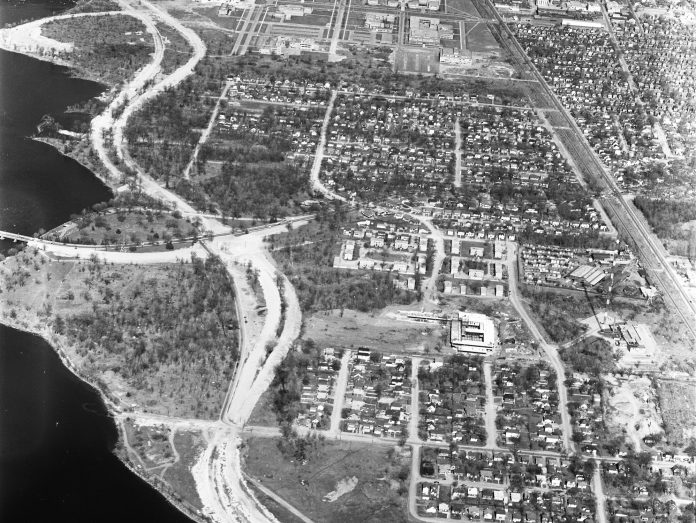

The most significant challenge in constructing the Parkway was fill. Not only was the existing shoreline insufficient in several areas, but the Parkway itself was to be built above the high-water mark of the river. This required enormous amounts of fill to be trucked in and new artificial shorelines created. This is most evident by Woodroffe and McKellar Park (where parts of the Parkway today would have been underwater prior to the ‘60s), Mechanicsville (where the water used to come right up to Burnside Avenue), and especially at Nepean Bay, where almost all of the land that exists today north of Scott Street from Bayview to Preston was manmade in 1965-66. The fill in this area was trucked in from the excavation for the new NAC on Elgin, and what is now the O-train trench west of Preston Street.

The NCC designed the Parkway to be a tourist attraction and a scenic drive, and heavily promoted the three lookouts (then called “Overlooks”) at Remic Rapids, Kitchissippi and Deschenes Rapids.

They stated repeatedly that it was intended for sightseers, for “lengthy pleasure trips,”not rush hour traffic. It was specifically constructed so that the eastbound lanes were built at a higher elevation and drivers would have an unimpeded line of sight over the cars on westbound lanes.

Landscaping and trees were also integral to the finishing touches. The NCC transplanted 150 white pines from Gatineau in September 1965 for the median. Later that year, the NCC proposed adding a chain link fence alongside the length of the Parkway to keep pedestrians (and cars) from taking short cuts, but public outrcy forced the NCC to back down. Interestingly, the NCC also initially banned dogs and cyclists from the Parkway paths.

Fifty years later, Ottawa is in the midst of an equally significant series of projects that will reshape this same shoreline area. The redevelopment of LeBreton, Tunney’s and Lincoln Fields, the introduction of the LRT, less buses, and more cycling corridors will set the course for the next 50 years in the west end. The NCC has even proposed reducing Parkway lanes and relocating them further from the shore in some areas in an effort to provide residents greater waterfront access. The final price tag for the original Parkway was $13,400,000, but the biggest cost may have been in the way it permanently changed Kitchissippi’s neighbourhoods. There is reason for optimism that the mistakes of the past will be corrected in a significant way during these exciting times.

Dave Allston is a local historian and the author of a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have early memories of the area to share? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.