Public overdoses on Ottawa streets have become an increasingly common sight. But when they occur, lives are saved by naloxone, an opioid antagonist used to reverse toxic drug effects.

Ontario’s naloxone program began in 2016 just as Ottawa’s opioid epidemic reached a new peak. According to data from Ottawa Public Health, the number of emergency department visits due to opioid overdoses in the city were on a steady climb from 2009, reaching a high of 250 visits in 2016. In 2017, the number of opioid overdose-related ER visits skyrocketed to approximately 375.

In 2016 pharmacists were allowed to distribute publicly funded kits in large group trainings through the Ontario Naloxone Program for Pharmacists. Now due to new provincial policy, they will only be allowed to offer individual training sessions in pharmacies only.

“The real value in having kits, not just in public spaces, is to motivate people to help another person,” said Ottawa pharmacist Mark Barnes. “My goal is to motivate individuals to get naloxone, but I can’t give it to them if they’re not willing to come to a pharmacy and that’s where I want the program to change.”

Barnes and his fellow pharmacist partners opened Respect RX pharmacies across Eastern Ontario where they provide inclusive pharmaceutical services. As its director of community outreach and overdose prevention, he has seen firsthand how group training can save lives.

In mid-February, a young male asked for a naloxone kit during an overdose prevention seminar. But because of the new laws, Barnes was unable to provide one on the spot and asked the user to get one at a pharmacy. He said the youth died three days later from an overdose.

“If I had given him the kit because he was using (drugs) with his buddies, he would still be alive today,” said Barnes. “His death, I believe, is due to these changes. It’s producing barriers.”

After months of pushback, an updated executive officer notice was released by Ontario’s health ministry that will allow pharmacists to train individuals virtually and deliver naloxone to those who physically cannot get to a pharmacy. The order will go into effect on Sept. 3.

But rising costs have meant Ontario can no longer provide naloxone kits for free. Each range from $110 to $150 and contain two naloxone doses. Because the reversal is temporary, individuals can continue overdosing while the drugs are still in their system, and often require more than one dose to be revived.

Dillon Brady, Carleton University’s manager of student conduct and harm reduction said it “feels like a pulling back at a time where it’s important to make naloxone easily accessible.”

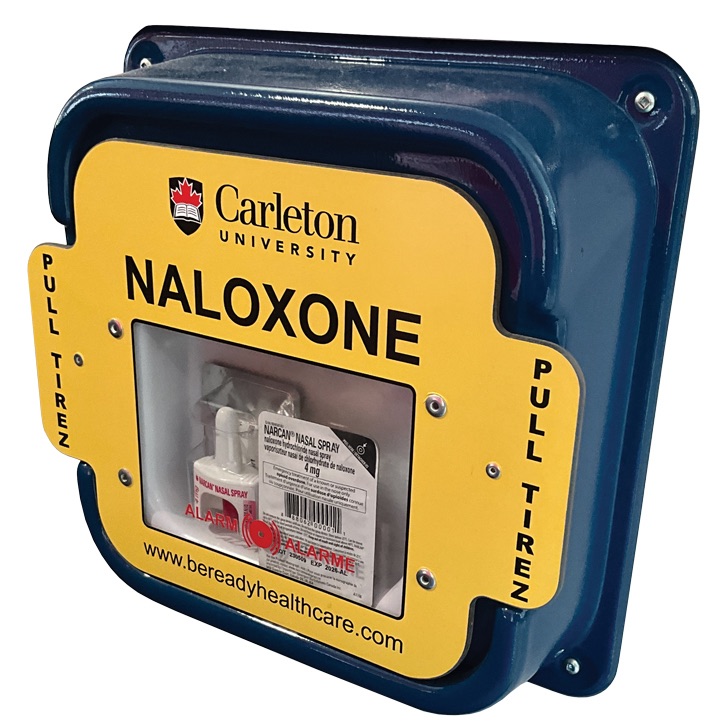

The university is one of many organizations that was included in the Ontario Naloxone Program and received free kits from the government. This allowed it to install up to 19 emergency boxes across campus and provide staff and students with kits after completing naloxone group training.

Brady plans to add seven more boxes, but he said that he foresees those being difficult to maintain.

“Unless things change, we are going to have to purchase that at an additional and unexpected cost to the university budget at a time where (it’s) already facing a number of financial constraints,” he said.

Educating people and challenging the stigmas regarding drug misuse is one of the greatest preventative measures of overdoses, say advocates. But Barnes said there needs to be systematic, multilevel changes for how this is delivered.

“It begins with empowering youth to make their own health decisions. We need to tell them not to use alone, and if they use, to carry naloxone with them, and that when they are ready, we are here to support them,” he said.

Sparking conversations about drug misuse in elementary school involves explaining to youth that people use substances when they may be going through something, but that doesn’t make them bad people. As youth get older, Barnes said they should learn that it’s a mental health condition, not a character flaw.

“All across Canada, almost 70 per cent of people who overdose are housed and over 70 per cent have a job,” said Barnes. “It’s not what you think. It’s grandmothers making mistakes with their prescriptions. It’s miscalculations in palliative care. It’s kids who get access to tablets.”