By Dave Allston

In a short span of time, the COVID-19 virus has changed all of our lives significantly. Our schedules, our routines, our way of dealing with others (even friends and family) has been altered in a major way. It arrived suddenly, overwhelmed an unprepared population and left government officials scrambling to make decisions to slow the spread of the pandemic. All of which bear eerie similarities to the Spanish influenza a century ago.

Though the viruses themselves are very different, the speed, spread and severity of the virus are comparable. The Spanish flu pandemic — or “Spanish Lady” as it was known — infected 500 million (about a quarter of the world’s population at the time) from 1918 to 1920. Inconsistent records have left a wide-ranging death toll estimated anywhere from 17 million to as high as 100 million. Spain was not actually its place of origin, but the moniker was associated with Spain as the source of the earliest reports of the pandemic. At the time, the flu was spreading in other countries but they were engaged in WWI. Spain was neutral in the war and had a free press.

Unlike COVID-19, the mortality rate of the Spanish flu was highest for adults under the age of 50. The flu was terrifying in its attack, with (then) no known causation or cure. The timing was also awful, with WWI raging and many Canadians fighting overseas, further straining living conditions back home.

The flu hit Ottawa in September 1918. At first, even the provincial officer of health, Dr. McCullough, downplayed the flu.

“There is altogether too much made of the seriousness of this Spanish influenza”, he declared on September 24. “Everything possible has been done to prevent its spread.”

How wrong he would be. Within a week, the flu was everywhere in Ottawa and the surrounding areas. Yet even then, top local physicians initially refused to acknowledge it as the Spanish flu. Hintonburg’s Dr. I. G. Smith stated to the media that the flu and its symptoms were no different from any of the flu breakouts of the previous 20 years.

However, once the pandemic took over, authorities were astonished at its virulence. One prominent Ottawa Doctor stated it “struck the town like a cyclone,” — it was spreading at phenomenal speed.

Initial chills, headaches and back pain would lead to sore throat, severe neck pain and, most concerning of all, high fevers of 101-104 degrees. The sick would weaken quickly, and the flu became fatal within days, even for (and especially) healthy, young adults.

Ottawa’s Board of Health issued a warning on September 26. The cyclone had taken flight. Seven Ottawans died over the first weekend, yet public officials still pressed for calm. On October 1, Dr. McCullough still claimed the pandemic was “overrated,” and that the “public should not be unduly alarmed about Spanish influenza.” The doctor recommended that citizens simply avoid close contact with those who appear to have colds or influenza, and stay away from public gatherings and crowded street cars.

The cases skyrocketed and the morgues began to overflow. By October 8, there were 58 dead with an estimated 4,500 reported cases, all this before the worst two weeks had begun.

Just as in 2020, the government issued orders to stem the spread. The Board of Health closed schools and theatres and, eventually, churches, pool halls and bowling alleys. Retail merchants — except for grocery, drug, stationery and book stores — were required to close shop at 4 p.m. Civil servants were ordered off the job by 3 p.m. Major sports events were cancelled, including an international plowing match (despite the protests of organizers). Streetcars were required to keep ventilators open, limit passenger counts to the number of seats, and each were fumigated with formaldehyde daily.

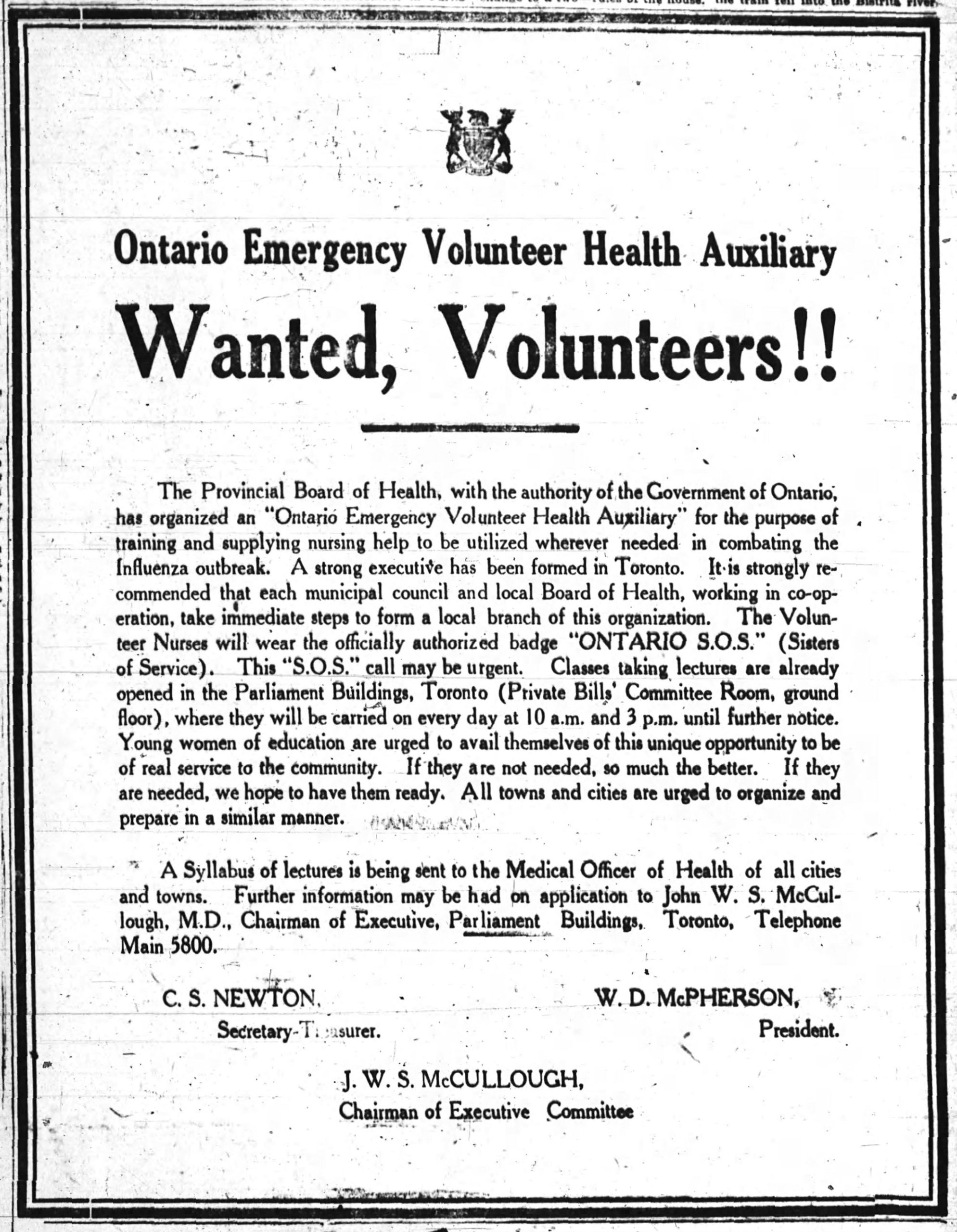

City hall was converted into a makeshift response centre for coordinating care with volunteers, clothing production (sewing teams of 150 were producing 1,400 articles of clothing per day) and dispersal of food and medicine. Some schools and buildings were converted to emergency hospitals, and every available health care worker, even those retired or in early stages of training, were called to duty. Eventually, any available woman or girl was asked to help manage the relentless demand. The Boy Scouts were recruited to deliver a pamphlet on prevention to all 27,000 households in the city.

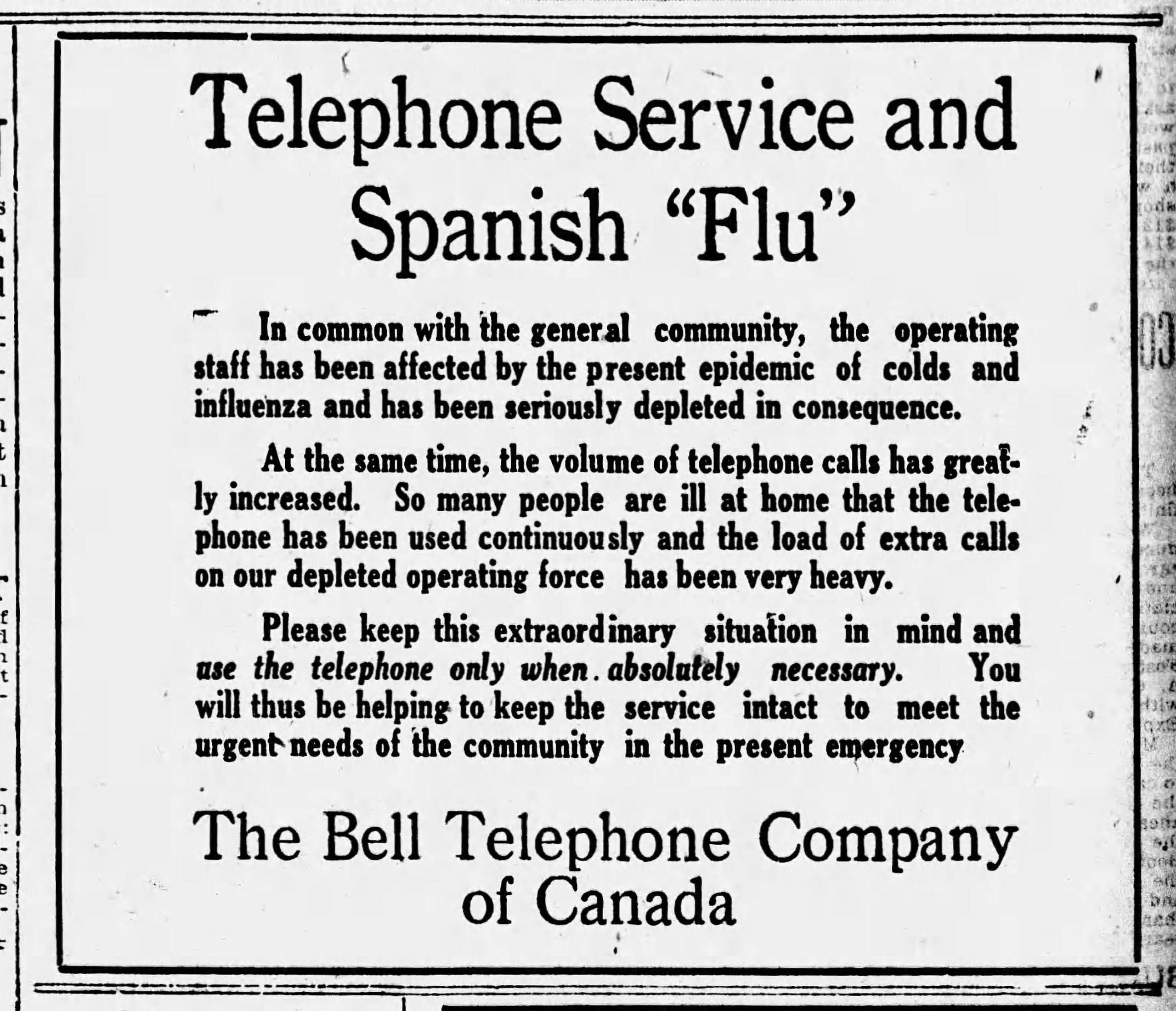

The Bell Telephone Company lost many employees to the flu. Yet with so many people ill and isolated at home, call volumes exploded, leading to a public warning to use telephones only when absolutely necessary.

Hospitals were overfilled, nurses visited homes in appalling condition. What scared citizens most of all, and was sensationalized by the media, was the potential for the flu to strike entire families. There were numerous reports that families of six or seven all had the flu.

At its peak, there were 600-700 new cases being reported a day. In a three-day period between October 16-18, 136 died in Ottawa. The long lists of the dead appeared ominously next to equally lengthy lists of war casualties in the local newspapers.

The flu hit Kitchissippi harder than most areas of Ottawa.

Kitchissippi’s sick were cared for differently based on a geographic split at the time. The city limits ended at Western Avenue (so named for this reason), so residents of Hintonburg and Mechanicsville could be cared for at Ottawa hospitals and receive aid from the Ottawa efforts. However, with houses built tightly together, and with a significant portion of the residents working hard labour jobs, the flu spread easily. Dozens of lives were lost in these neighbourhoods, including siblings Harry and Muriel Marier (three and one-years-old, respectively) who lived at 15 Oxford; two-month-old Florence Plamondon of 12 Stirling; and 33-year-old Dr. Alexander Tilley of Spadina Avenue, to name just a representative few.

Westboro arguably suffered more than any other neighbourhood at the onset, for no particular reason. 28-year-old Bernard Wait of Duncairn Avenue was the village’s first victim on October 2. Two days later, 20-year-old Mary Ellen Dancey of Athlone Avenue passed away, leaving behind her husband she had married only in June. A day later, 28-year-old Lola O’Neill, Sunday school teacher and clerk at the Westboro Post Office died, as did one-year-old Ella Hall, daughter of a Westboro blacksmith.

The reports over the following days for all Kitchissippi (and Ottawa) were all the same; young residents died from influenza, after only days of illness.

For the residents of Westboro and beyond, the Township of Nepean had to spring into action, which it did in impressive form.

A relief committee was appointed by Nepean Council on October 15. Nepean residents requiring help were asked to phone the town hall so officials could gauge the severity of the situation. The results were staggering, with reports from Westboro and Woodroffe being especially dire. Calls for volunteers for nursing and other work were urgently put out. “Girls and more girls, is the cry” noted the newspaper. Cars were needed for transporting nurses, clothing and food to all areas of Nepean, where the epidemic was prevalent in all corners. A large team of women made clothes at the town hall.

Most notably, an emergency hospital was established in Westboro. A large brick house (what is now 404 Athlone Avenue) was secured by the committee and converted into a makeshift hospital. Dr. Leonard L. Derby of Westboro was put in charge. The house was initially fitted up with 12 beds and opened on the afternoon of Friday, October 18, with seven patients. Within days, capacity was increased to 18 beds. A second house was acquired, to expand the hospital if required, and the town hall was readied in case it too would be needed (thankfully neither were). The hospital treated a total of 24 patients in its first ten days, thanks to five full-time staff and 12 part-time volunteers.

The hospital, and the actions of the relief committee, proved to be a huge success in calming the epidemic in Nepean. By early November, the pandemic had largely subsided in Nepean Township, and the hospital was no longer required by January.

In fact, the entire epidemic across North America largely subsided by the end of the year. In Ottawa, restrictions were lifted by mid-November, the final death toll standing at 520. It was estimated that in all, 10 per cent of Ottawans had suffered the flu.

It was thanks to the fast and thoughtful actions of local government that the pandemic was quelled so quickly, and the number of deaths kept relatively low. The impressive work of the volunteers and their coordination cannot be understated. Let’s pray that the actions of government and community alike in 2020 reap a similar result.