Commemorating the Boat People who fled Vietnam after the war was merely a dream for Vietnamese immigrant Can Le.

In 2007, Le’s vision became his vocation when he developed plans to create the Vietnamese Boat People Museum at the corner of Preston and Somerset Streets. With over 15 years of delayed progress, the project lead and his supporters are adamant that construction will commence in the next few years.

“We have set for ourselves an objective and everyone agreed that it would be a good idea. The museum will be built one way or another because there is strong support from the community,” a hopeful Le told KT.

When Canada announced it would accept 8,000 Vietnamese refugees in 1979, former Ottawa Mayor Marion Dewar pledged to welcome half of them to the city. This endeavor is known as Project 4000.

The initial concept for a Vietnamese community space was inspired by the overwhelming success of the 25th anniversary of the non-profit’s mission in 2004. Le wanted to organize a permanent installation where people could learn about the Vietnamese diaspora.

“Originally, we planned to have an exhibition for two weeks but so many people came, including the younger generations, the children of the refugees, sponsors, and the general public,” said Le. “There was so much interest in the exhibition that we extended it to five weeks. We decided that we could organize an exhibition like this from time to time, but there should be a long-term solution and that was going to be a museum.”

Le was one of many community members who helped create orientation programs, find jobs and housing for newcomers, and matched volunteers with sponsors to increase community support.

As more people arrived, Le’s work in the community increased. He organized conversational English classes to help the Vietnamese community overcome language barriers and opened Ottawa’s first Vietnamese Centre at 249 Rochester St.

Along with presenting the historical background of the Boat People diaspora in the museum, Le wanted to showcase the community’s achievements and contributions in the time since.

Delayed by a decade

Le and his supporters began fundraising for the museum from coast to coast and across the United States in 2008, receiving “overwhelming” support.

By 2014, the project had such traction that competitors sought new leadership of the project, the expensive addition of underground parking, and for the museum to be built in Edmonton instead. The heated disagreements soon became a pricey court matter.

To pay off a whopping $30,000, Le used a combination of his personal assets and the funds he raised for the site. In 2019, the court sided with Le but this chapter did not fully come to a close until 2021 when the defendant lost their chance to appeal.

Along with the challenges of the pandemic, Le also revealed that he suffered a stroke, which further delayed progress.

Following the pandemic, Le revisited his dream and began taking concrete steps by hiring consultant Saide Sayah in 2023 and architect Jessie Smith about a year later. The group is currently finalizing a design plan which will determine cost estimates.

According to Smith, the Saigon Square building is set to be six storeys to accommodate the three-storey museum and 15-20 residential units above. Once inside, people will be greeted by the memorial hall and a commercial space, likely for a cafe.

“There will be a big celebratory stair that wraps up to the second floor which will have the gift shop, maybe a service centre, and a library,” she said. “On the third floor, there will be three exhibition rooms.”

Both Sayah and Smith agree that cost is the biggest hurdle with this project, but that it will add tremendous value to the community.

“Construction prices post-pandemic are still high and I think a lot of it will depend on their ability to fundraise,” said Sayah. “We’ll look at how much rent the dwelling units could bring in or if they’re eligible for some kind of affordable housing grant.”

On November 3, Le is holding an event to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Project 4000 and raise funds for the Vietnamese Boat People Museum.

A harrowing journey

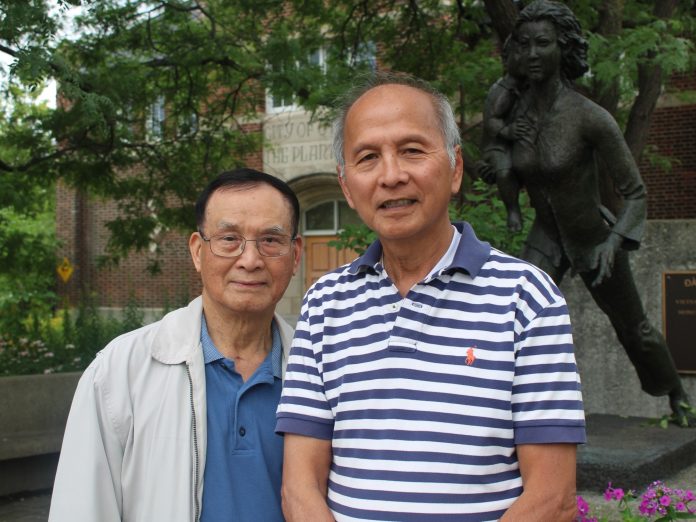

While Le is not a Boat Person, some of his greatest supporters are. Building a museum to memorialize the almost 800,000 people who fled the war not only preserves their history but ensures newer generations are taught the reasons and difficulties of their ancestors’ exodus.

Le’s longtime friend Liem Duong left his fiance behind to board a cramped boat of 48 people, some of whom did not survive the journey.

“It took 11 days because there was a typhoon. People died on the boat,” Duong recalled. “We planned on the trip taking four days according to the navigator, but with the typhoon and the boat’s engine problems, it took us 11 days.”

His 11 months on an island refugee camp were no less grim.

“At that time, the United Nations Refugee Agency sponsored us but we were stateless, meaning we had no country,” said Duong. “You’re not from Vietnam anymore, you’re not from Malaysia. You’re nothing.”

After five years of journeying alone, Duong was finally reunited with his fiance in the late 80s, a few years after he settled in Canada.

An Hoang, another Boat Person, was so overjoyed when he finally immigrated to Canada. He had fought in the war for years and when he finally escaped, pirates raided his boat three times and killed about 30 people.

After three months in a refugee camp, Hoang finally got his fresh start in Canada.

“Me and two other Boat People rented a one-bedroom. My two friends went to school every day, but I went to work,” Hoang said. “I worked in the kitchen to make money to send back to my family. Later on, I sponsored my parents, and then I later sponsored my younger brother, and finally, I sponsored my fiance.”