By Dave Allston –

In many ways, Kitchissippi still had a very rural, village-like feel as late as the 1970s. This is perhaps no better exemplified than in a unique event that brought tens of thousands of Ottawans to Kitchissippi every year: a professional dog sled derby! Long-time residents of the west end likely have vivid memories of lining up along Byron Avenue each winter to watch traditional dog sled teams race along what is now Byron Linear Park.

Dogsledding, of course, has a long history in Canada. Derbies became popular after WWI and especially in the 1930s. They were even included as a demonstration sport at the 1932 Winter Olympics. Ottawa’s first major derby took place in the 1930s. The route of the International Ottawa Dog Derby began at the Chateau Laurier and ran along the Queen Elizabeth Driveway, then along Carling Avenue toward Bells Corners and Fallowfield Road. It was a regular part of the Ottawa scene until unpredictable winters killed the event in 1956.

In 1959, Kitchissippi saw its final streetcar travel through its streets, and by the spring of 1960, the tracks had been pulled up. From Holland Avenue all the way out to Britannia stretched an open tract of land without a known future.

In late 1962, the Kinsmen Club of Ottawa (a group similar to the Rotary Club) came up with an idea to revive the International Dog Derby and have the course run along the former streetcar right-of-way.

A year later the event was added to the schedule of the Ottawa Winter Carnival, which was inspired by Quebec City’s famous carnival and newly established in 1962.

On Friday February 15, 1963, 14 teams from the U.S. and Canada met on Byron Avenue at Holland Avenue, the starting point of the two-day, 12 mile-per-day race. Teams were released at three-minute intervals. The course took them the length of Byron, crossed Richmond Road at Richardson Avenue, and continued along to Britannia where they entered the icy Ottawa River, mushed a two-mile circle, and then returned along the same route to the finish line at Holland Avenue. A prize pool of $1,000 was provided, with $300 going to the first place finisher, Keith Bryar from New Hampshire, who completed the course in about 40 minutes each day.

The dog derby quickly became the most popular event of the carnival, which featured other highlights such as barrel rolling competitions on Rideau Street, teen dances on ice, tug of war on Sparks Street, Pushball on Bank Street (in which participants pushed an enormous 6-foot high ball), 24-hour skating marathons, skydiving, and the ever-popular motorcycle races on the canal at Dow’s Lake.

At its peak in 1969, the derby had 57 dogsled teams comprised of 458 dogs (85% of them huskies), with teams coming from as far away as Alaska. A second division was established in 1968 for less competitive entries – a “novice” division – which raced only to Richardson Avenue and back. Entries in the novice division used just three to five dogs, while teams in the professional division typically used at least 12 and up to 15 dogs.

A large quantity of snow was key to a good, fast race. The city trucked in snow to provide extra padding on the course during years of low snowfall.

The starting line would have been a scene of great excitement. As one reporter noted: “the plaintive cries of huskies filled peaceful west-end suburbia. The beautiful canines were just howling to get in on the action.”

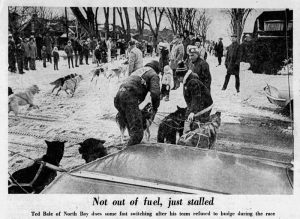

The sleds travelled at speeds of around 15-16 mph. The driver pumped scooter-fashion at the start to gain initial momentum and shouted turning instructions at the dogs: “gee” for right and “haw” for left. It was noted that a good musher had to watch out for a single dog tiring. Failure to respond instantly to a command during a race could result in a tangle, which could cost the team precious minutes.

The derby was hugely popular and became one of the biggest competitions in eastern Canada and one of the few in the world held within a metropolitan area. It created major traffic issues, particularly in the Wellington Village area when onlookers crammed in to view the start and finish lines. In its most popular years, crowds approached the 40,000 mark. Police were on hand to ensure people stayed off the course and organizers warned fans to leave their own dogs at home. “Last year a couple of pets got a little too close,” noted a newspaper in 1968. Police were especially concerned in 1970 when a dog was stolen from a truck after the race from a parked truck on Holland Avenue. The dog was considered “unreliable,” and its owner noted, “it’s not a pet, it’s just a sled dog and not really used to people.”

After the competition, a dance and dinner (“the Mushers Ball”) was typically held at Ukrainian Hall on Byron Avenue or at Lakeside Gardens at Britannia.

[Click photos to enlarge.]

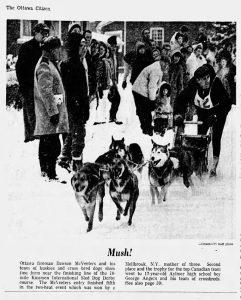

Ottawa’s own Dawson McVeetors was the event’s most popular figure, winning the 1970 race after eight years of trying (he also won in 1973). He declared himself a “mongrel man,” and contended “mixed breed dogs, properly trained, are just as good or better than purebred huskies.”

Despite the sport being dominated by men, 37-year-old Anne Wing of Millbrook, New York, won the 1967 main event. Second place finisher George Angers was a 17-year old student from Aylmer who ran a team of just six crossbred dogs. His strategy was to run the majority of the course himself, and in a display of incredible athleticism, when the team began to slow near the end of the race, he ran to the lead dog and pulled her across the finish line.

The 1970 novice event was won by 9-year old Gerry Perusse of Clarence Creek, who also won in 1971.

By the summer of 1972, the Ottawa Winter Carnival was in trouble. The carnival chair announced it was a waste of money and that the $100,000 budget could be better used to host events throughout the winter, rather than over one weekend. The 1973 budget was slashed, attendance went way down, and the city pulled the plug. The Kinsmen ran a successful derby on their own in 1974, but drew (undue) criticism for using some of the proceeds from the sale of buttons and tickets to subsidize the race (just to cover what the city no longer paid!), rather than donating it all to charity. The Kinsmen withdrew, marking the end of the derby. That same summer, the city began to create park space and plant trees in the former streetcar tract, officially bringing an end to the era of the Kitchissippi dog sled derby.

Dave Allston is a local historian and the author of The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have early memories or photos to share? Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.

*This feature is brought to you in part by Jamari Espresso House, the coziest coffee shop in Hintonburg, and Produce Depot.