By Dave Allston –

As McKellar-Bingham House on Richmond Road begins to approach 200 years of age, its colourful history is emblematic of the development of the area. Home to several pioneer west-end families, it has stood the test of time thanks to the initiative of key individuals at key times. Ironically, though it is one of Ottawa’s most notable heritage homes, the history of the mansion has been regularly misreported. Even its official plaque is incorrect.

Occasionally confused with Maplelawn (a.k.a. Keg Manor), its former next-door neighbour, McKellar-Bingham House actually bears the names of its fourth and fifth owners.

The Thomson family arrived in 1818 and constructed the impressive Maplelawn stone house (1831-1833) on Nepean Township lot 29, shortly before patriarch William Sr.’s death. In 1828, two of William’s sons, John and William Jr. purchased neighbouring lot 28 to the west (John later bought out William Jr.’s half in 1840). At some point in the 1830s, John built a log house on lot 28, half a kilometer west on Richmond Road from Maplelawn.

Records indicate that John built the stone McKellar-Bingham House as early as 1840 to replace his log house. It was built in a similar design to Maplelawn and likely by some of the same hands, including the Thomson brothers, who were considered master craftsmen.

John’s younger sister, Janet, was a young widow with a young son (William Thomson Aylen, born 1826), and the two moved in with John. John reputedly raised William like a son and upon his passing in 1853, left William almost all of his estate, including the stone house.

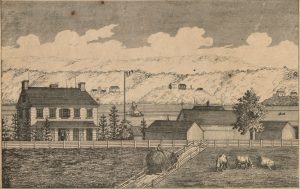

William Aylen went on to become one of Carleton County’s most esteemed citizens and top farmers, as evidenced by an illustration featured on an 1863 map of the county. He served as president of the County Agricultural Society in the 1860s and hosted large events on the farm including well-attended ploughing matches. In 1866, the property was sold to prominent Wakefield mill owner and Postmaster, Andrew Pritchard.

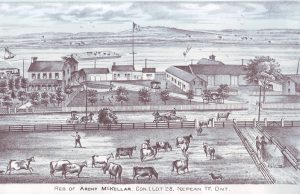

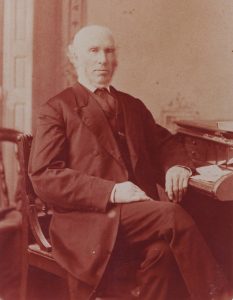

On September 23, 1873, Pritchard sold the farm for $32,000 to Scottish-born Archibald McKellar, a 60-year-old farmer who had operated a dairy farm on leased land on the Billings Estate for 30 years. McKellar had carefully chosen the Westboro-area farm and mansion as his first-owned property. He continued on as a successful dairyman, farmer and stock grower, and his homestead was a showplace. When Archibald passed away in 1889, his 45-year-old son John took over operations.

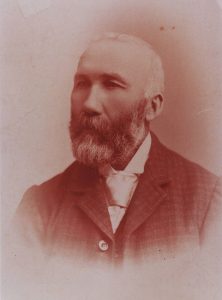

1911 was a significant year in the transition of the neighbourhood, as McKellar retired from farming. He built a smaller stone house just to the west (later known as the Wayside Inn) and sold the original stone mansion to John Bingham, director of the Ottawa Dairy Company. He then sold the bulk of the farm to a syndicate who called themselves the “McKellar Townsite Company”. The company created a new subdivision of 15 streets and 1,092 building lots. John had no involvement but their name ensured “McKellar” was forever attached to the neighbourhood.

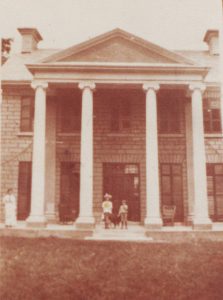

Bingham improved the house significantly. He retained the huge log beams that ran the length of the house supporting the ground floor, flagstone floors in the basement, copper roof, mahogany panelling, marble fireplaces, handblown original windows, and walls which were two- to three-feet deep. He removed the original latticed porches, replacing them with pillars in a colonial U.S. style. An old wood fence was replaced by a stone wall topped by iron grillwork. Plumbing was added through the old iron water pump along the east side of the house still pumped well water into the 1980s.

[Click images to enlarge.]

John Bingham died in October 1929 and his widow Addie remained in the house until her death in 1951. Following her passing, the family had a tentative deal with the CBC who wished to acquire the mansion to establish Ottawa’s first television facilities, but the deal was nixed, sending CBC to Lanark Avenue instead.

Radio station CKOY acquired the property in 1953 for $42,500. After the city opposed the use of the house for non-residential purposes, the Ontario Municipal Board overturned the decision, but ordered that the building could not be changed structurally from the outside, permitted only a small sign, and disallowed any additional construction on the property.

CKOY grew, adding an FM station in 1969 (CKBY) and as early as 1965 began regular applications to the city for much-needed expansion. Each was summarily rejected. CKOY stopped making minor repairs because major renovations were anticipated. As a result, the house was in a dilapidated state by 1978. Ducts ran through the front door, wires ran through doors, floors and windows throughout the house, the iron gates were decaying and the columns were cracked and crumbling.

CKOY publicly considered and eventually applied for a demolition permit, which prompted residents to push for heritage designation. The July 1978 designation ultimately saved the house. Future use was limited to residential only; no significant exterior alterations would be permitted and the view of the house from the street had to be preserved. This limited CKOY’s ability to remain in the house and also its potential sale price.

CKOY broadcasted from McKellar-Bingham House until December 31, 1978. Interested buyers had many ideas (embassy, nursing home, prestige restaurant, community space) but all insisted on the need to construct townhouses or condos as part of the development plan for the 2.3-acre site. The sale was complicated by the city’s reluctance to allow non-residential special status as they had done in 1954. Precedent had also been set next door in 1976 when 52 garden homes were built in the Riverwood development surrounding the old Hutchison House (built in the 1920s as a wedding gift from John Bingham to his daughter, Lillian).

In a controversial move, the city purchased McKellar-Bingham in 1980 for $515,000 to ensure protection for the house and to control its future use. Neighbouring community associations fought valiantly against the development of the surrounding townhouses, but succeeded in limiting their height to 11 metres, while also prohibiting commercial use.

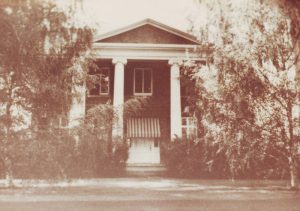

The city, though doing admirable work in preserving the mansion, took a $200,000 loss in interest and fees when it sold the property in 1982 to developer Roboak Developments. Twenty-two condominium townhomes priced from $165,000 were constructed over the winter of 1982-1983. The development, called “Bingham-McKellar Estate,” was advertised with the slogan: “A historical landmark destined to become a residential hallmark.” McKellar-Bingham House was renovated in 1984 and divided into six condo units with 16’ ceilings. The columns were replaced with a wood verandah, restoring the house to its 1879 appearance. It’s a good example of a developer preserving a heritage structure while developing the parcel of land. Other developers should take note.

Dave Allston is a local history buff and author of The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have stories to share about the area? Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com. To read more of Dave’s columns, click here.