By Dave Allston

Ottawa Neighbourhood Services was once a Hintonburg mainstay. For nearly 90 years, the Kitchissippi-based organization supported the community’s less fortunate, who depended on its programs the most during the Christmas season. But it has quietly disappeared over the last few years. Now, it exists only as a memory.

The flagship store and workshops were located on Wellington West in buildings now home to the LCBO and Maker House. Ottawa Neighbourhood Services (ONS) provided free clothing, furniture and appliances to those who needed help. It also employed people with disabilities, who otherwise had difficulties finding work.

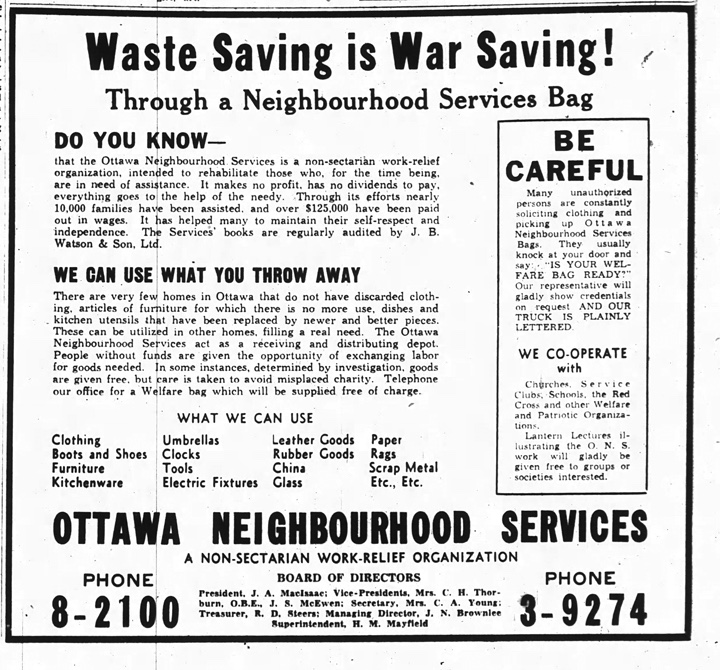

Its roots in the community date back to winter 1932 when the Great Depression slashed welfare assistance across the continent. Edgar Helms, a minister in one of Boston’s poor neighborhoods, had established Goodwill Industries in the United States 20 years prior. The program was designed to convert “waste into wages” and “junk into jobs”.

Helms soon met Harold Morris Mayfield, a 38-year-old with a shared interest in helping the less fortunate, who had recently returned from England after serving in the First World War. Inspired by Helms to open his own charity, Mayfield moved to Ottawa and rented a room on Queen Street. After several weeks of trying for a partnership with churches and service clubs, he gave up and booked tickets back to England. But a last-minute meeting with Norman Coll, pastor of Parkdale United Church, gave Mayfield encouragement to stay and establish Ottawa Goodwill Industries.

He used his own money to rent a small store on Wellington Street West across from St. Francois d’Assise Church. The new organization used a room in the back as a workshop and hired three young boys who slept at a nearby hostel. Mayfield provided them meals cooked on the one small stove in the building.

Meanwhile youth from Parkdale United helped Mayfield distribute the first 200 “welfare bags” of used clothes to churches, service clubs and private homes.

Mayfield woke before sunrise, hitched his horse Daisy to an old rig, and travelled around town collecting donated furniture and clothes. In the afternoon he ran a thrift shop that sold items to people who could afford them, and gave them away to those who couldn’t. At night he washed and mended clothing he had picked up that morning in a second-hand washing machine and prepare the clothing for the store for the next day. He later upgraded to a $45 used truck to replace his horse and rig.

Ottawa Goodwill became a success. In December 1932, Ottawa’s Public Welfare department asked Goodwill to become the distribution centre for the city’s 2,000 families on relief. At the insistence of Welfare Director Charlotte Whitton (later the City’s mayor), Goodwill was renamed Ottawa Neighbourhood Services.

Mayfield briefly moved operations from Hintonburg to Byward Market from 1933 until 1936, and then to the corner of Wellington and Garland.

An early fundraiser was a charity hockey game in early 1933, with Ottawa Senators versus senior city league players. The price of admission was a bundle of old clothes. ONS received eight truckloads, sold most items to cover costs, but always set aside a sizable amount for free distribution to those who couldn’t afford it.

In 1937, the ONS became a private welfare agency; after the Second World War, it started hiring people with disabilities and providing them with workshops to develop employable skills. In the early years, Harold Mayfield taught shoe and furniture repair, as well as dressmaking and repair of appliances. For many years, the entire staff of the Wellington Street plant had mental or physical disabilities and were unable to work elsewhere. But a notable success story saw a former employee opening their own similar shop.

“There have been times where difficulties and discouragements have made us wonder if it was all worthwhile,” Mayfield said years later. “Then we would go on a tour of the workshops and watch men and women happily working who might be unemployed if it were not for ONS … back to work we would go with a greater determination than ever to increase our service.”

Harold Mayfield’s wife Marjorie, who worked in the offices, spoke in a later interview about the children who came to ONS.

“They looked so scruffy, dirty and cold. We took them into the school clothing room and washed their feet,” she said. “We gave them new underwear, clean clothes, warm boots and a warm coat. It was so good to see them look happy and warm when they left. It is a memory that will always stay with me.”

ONS eventually took over the entire block of Wellington Street. For years, they worked through increasingly challenging conditions in the decaying old buildings.

In 1964, Mayfield’s long-held dream finally came true when ONS demolished the old structures and constructed a new building at the corner of Garland.

The new $500,000, four-storey Mayfield Building opened in May 1965. On that day, Mayfield estimated the organization had helped more than 22,000 adults since 1932.

Knowing the future of the organization was well set, Harold retired four days later, and stayed on as an adviser before passing away in 1975.

In 1966, ONS installed collection boxes (likely the first of its kind in Ottawa) at Westgate and Shoppers City malls to make donating easier.

The ONS opened branch stores in other areas of the city amidst increasing competition. By the mid-1990s, around 400 thrift stores were established in the region, including Salvation Army, St. Vincent de Paul, and the U.S.-based corporations Value Village and Goodwill. As well its clothing donation bins were accompanied by an explosion of bins set up by out-of-town for-profit companies, and ONS supplies dwindled.

ONS fell into bankruptcy protection in 1998, and sold many of its buildings, including the Wellington headquarters. Then-director Dave Smith said they walked away with a “bag of pennies.”

The thrift store moved to Richmond Road near Lincoln Fields in 2001, but relocated to an industrial bay at City Centre in 2007 when their building was sold. In 2012, they were the victims of arson. They moved to Rideau Heights Drive, a quiet dead-end street with no walk-by traffic and limited bus service.

Within a few years, ONS fell behind on rent and volunteers, and became dependent on private donations. They were evicted from Rideau Heights in May 2016 and survived briefly without a storefront, but disappeared altogether during the COVID-19 pandemic.