Looking to play pool or snooker? You likely have to go outside of Kitchissippi to do it. Rising commercial real estate costs have sadly made pool tables a rare sight within the ward’s borders, with just a single lonely table at the Carleton and a pair of tables at the Westboro Legion.

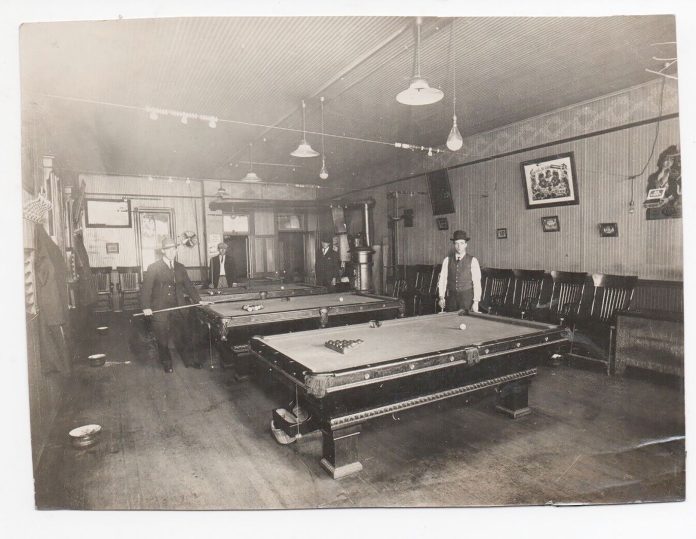

A century ago, neighbourhood residents faced the same problem, but for very different reasons. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, pool halls were considered one of society’s greatest evils. The battle to open a pool room in Hintonburg was a long and fierce one, which pitted blue collar workers and teens with limited recreational options against local politicians, churches and community groups for many years. Pool halls were long seen as a venue for lower class men to congregate, where gambling, drinking and swearing was commonplace. For taverns, licensing of pool halls fell to each municipality, many of which were happy to exercise their right to refuse.

The oversight of billiards in Ottawa goes all the way back to 1850 when Bytown Town Council passed Bylaw Number 12, introducing the licensing of “billiard tables, ball alleys, skittle alleys, nine or ten pin alleys and also pigeon holes and bagatelle.” An annual fee of seven pounds, ten shillings was due for every hall or house where these games were played. Failure to pay the fee was a five pound penalty “or be imprisoned within the County Jail for a period not exceeding one month.”

In the 1850s, Murray’s Billiard Room at the corner of Sparks and Metcalfe became a popular place to play, and even featured a saloon at the rear, known as “The Office,” with “the best of liquors and cigars always to be had at the bar.”

These venues were contentious, looked down upon by religious and community groups, who fought their opening. During a rousing sermon in front of a packed house at Dominion Church in downtown Ottawa in February 1888 Rev. Hunter preached of the evils of “the Three Bad B’s… billiard rooms, bar rooms and blasphemy.”

A few did open in the late 19th century, like McCaffrey’s Amusement Hall on Queen Street, the Grand Union Billiard Hall on Elgin, and the billiard room inside the Russell Hotel. Kitchissippi though, remained poolroom free.

Paul Pelletier was an experienced pool hall proprietor from Quebec when he opened Hintonburg Village’s first pool room in March 1905 in the new ”Jones Block” building, in the fancy new digs of what is now Hello Dolly at 992 Wellington at the corner of Irving.

In the spring 1904, the Ontario legislature was concerned about Americans coming across the border and establishing gambling dens out of pool rooms in Canadian towns. Meanwhile in the States, pool rooms were under fire as most were being used for off-track betting. Western Union nearly set off a civil war when they shut off telegraph service to pool rooms, which were dependent on them for race updates. A “war on pool rooms” was declared in New York City that spring as 22 pool rooms were raided in one afternoon, resulting in 70 arrests and the seizure of telephones, telegraph machines, books and racing charts.

In April 1905, Ontario Premier Whitney targeted pool rooms, particularly problematic ones in Toronto. The attorney-general himself oversaw the shutdown of the Toronto Junction pool room, after detectives had been tapping wires to the betting room for three weeks. Many accused the government of being hypocritical, wondering how gambling could be allowed and even encouraged (including by women and children) at Woodbine racetrack, yet were so swift to shutter pool rooms.

A short game of pool

In February 1907, brothers William and J.B. Duford applied for a license to open a second pool room in Hintonburg. The Village council was to consider it, but local citizens had clearly seen enough. At the next council meeting, local clergymen presented a petition against the pool room signed by 150 ratepayers, as well as an impassioned letter from Rev. Father Fitzgerald of St. Mary’s in Bayswater. The group not only opposed the new application but went a step further, asking Council to close Pelletier’s room.

“The pool room is an evil resort and should be put out of the village,” they claimed.

Councillor Bulllman supported them and put forth a proposal mirroring Quebec, raising licensing fees for each pool table. With the passing of Hintonburg By-Law 232, the license fee went from $5 to $100 per table.

The new fee killed the Duford plan, and when Pelletier’s renewal came up that spring, he closed shop. By June Pelletier was operating on York Street. His departure was gleefully reported by the Citizen: “The village has not suffered a heavy loss by the removal of the pool room. It is stated that it had become a rendezvous for boys and young men who might have been otherwise better employed.”

However, just months later, in fall 1907, Hintonburg became part of the city of Ottawa. The village now fell under city bylaws. No longer could the local clergy direct neighbourhood affairs so directly.

William Duford reapplied for a pool hall license. Competing petitions were submitted to Ottawa Board of Control. One had 288 ratepayer signatures supporting a pool hall, the other, 256 against. Rev. Father Fitzgerald wrote again, stating that many parents felt Pelletier’s room had been a “source of detriment to the morals of the young men.”

Though Mayor Scott and Controller Hopewell were “on principle opposed to public pool rooms,” other controllers suggested that it was unfair to block pool halls in one area of the city but not others.

The Mayor was skeptical. “I have nothing against pool if it is played under proper

conditions. I have nothing against the drinking of whiskey in the home, but if I could I would close up every saloon in the province.”

In the end, the license was granted and, ironically, the 24-year old Duford opened in Pelletier’s old spot at 992 Wellington. A year later he moved across the street to 987½ Wellington — the spot where Maker House exists today.

To counter Duford’s pool room, St. Andrew’s Church of Ottawa formed a new club, the “Hintonburg Social Institute.” Securing space on the second floor of the Fairmont Avenue fire hall, young men were invited to meet nightly “to play cards, read the current magazines kindly placed at their disposal by the St. Andrew’s Church Men’s association, or to converse in their well appointed room.”

The Institute held a formal opening on May 2, 1908, where Mayor Scott spoke, and promoted “that great benefit would be derived by all the young men of Hintonburg who made use of the comfortable rooms.” Later that month, Michael H. Fagan was elected president of the Institute, as the group began to organize baseball and football teams to compete in city leagues. It was abandoned two years later.

Mounting pressure

Duford’s pool room closed by mid-1911, but the same battle waged in other neighbourhoods. Glebe and Old Ottawa South residents banded together in 1912 to successfully fight a proposed pool room on Bank Street, in the highest-attended meeting ever held in the vicinity.

Following WWI, with prohibition in place in Ontario, there was reduced concern about pool halls (though churches were still hotly opposed). Between 1920-1921, two poolrooms opened across the street from each other: Alex Ristow at 1101 Wellington, and Emmett Brady and Arthur Richer’s room at 1100 Wellington.

Most memorable to long-time residents are the pool hall and bowling alley on the second floor of what is now Giant Tiger, then known as the United 5¢ to $1 store. Ristow opened the Recreation Billiard Academy there in 1932. It soon became the Fisher Athletic Club, then Fisher Billiards until it closed around 1967.

The Fisher pool room wasn’t squeaky clean, however. It suffered occasional raids, including in 1953 when police arrested 17 customers and seized over $1,000 in cash and three truckloads of gambling furniture.

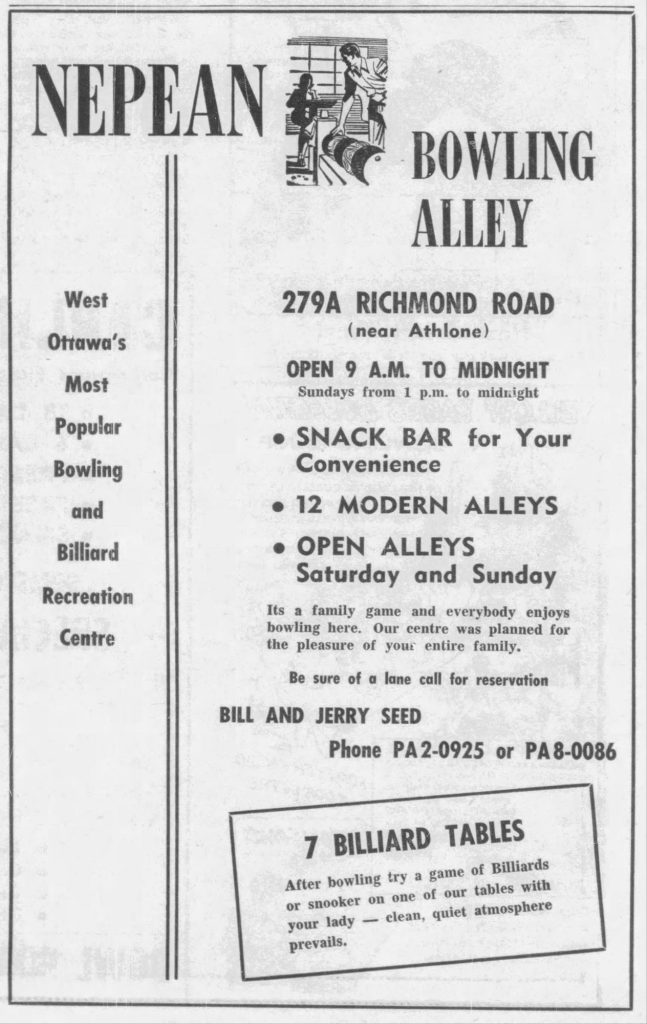

On the other side of Kitchissippi, Omer Major opened the Westboro Bowling Academy in 1931 in Benjamin Bodnoff’s building. After WWII, Bill Seed’s Nepean Recreation Centre — later Nepean Bowling — opened at 279A Richmond Road

Wellington Village had a pool hall for a number of years, the Broken Cue — later the Albertan — operating out of 1310 Wellington Street in the 1970s.

Other notable names from the more recent past include Minnesota’s at 203 Richmond Road — now Bushtukah — and smaller venues like the Easy Street Café and Puzzles in Westboro, all three of which I spent a lot of time in after school in the ‘90s.

Today, the Orange Monkey at nearby City Centre (opened in early 1989 by three Carleton University students, and named for one of their nicknames) remains a bit of a throwback to the early days of pool rooms. Just too bad we have to leave Kitchissippi to get to one.