By Dave Allston

The intersection of Gladstone and Loretta is steeped in history, as many will identify the soon-to-be-designated Standard Bread building as an important piece of west end history.

However, there is another key part of early Hintonburg history, largely forgotten through time, that stood at this corner as well.

By the late fall of 1899, Hintonburg’s development was full steam ahead. The CPR and GTR railways were bringing blue-collar workers to the area as fast as they could build. Former farmland was being sold at a terrific pace to keep up with the demand. Streetcar tracks were being laid through the village, which would establish Hintonburg as an easily-accessible hub to both the city and the burgeoning neighbourhoods to the west.

Perhaps most importantly, the Hintonburg waterworks system began pumping water throughout the village, enticing industry to come set up shop in the vast (and cheap) available land.

Just one week after the water began to flow a land deal was made between the Nicholas Sparks estate (the original landowner and subdivider of the “Bayswater” section of early Hintonburg) and a well-respected Ottawa furniture manufacturer, J. Oliver & Sons. The furniture manufacturer agreed to purchase a five-acre lot in a quiet, isolated part of the subdivision for $4,200, on which they immediately began building a three-storey factory.

On December 6, 1899, the day that Hintonburg’s water was deemed “quite fit for use, as the flavor of tar has disappeared”, work began extending the pipe for the Oliver factory, located on the south side of what is now Gladstone (then known as Willow, though soon after renamed Oliver Street) and the east side of Loretta (then known as Second Avenue), now the site of a newer commercial building featuring Studio S Interiors (formerly Auto Trader).

At 120×45, it was a significant structure for its day and became an important piece of the industrial growth of early Hintonburg. Its success would later influence firms like Standard Bread and Beach Foundry to set up shop in the village.

Construction moved quickly throughout the winter of 1900, and by early May the factory was in operation, with 40 employees to start.

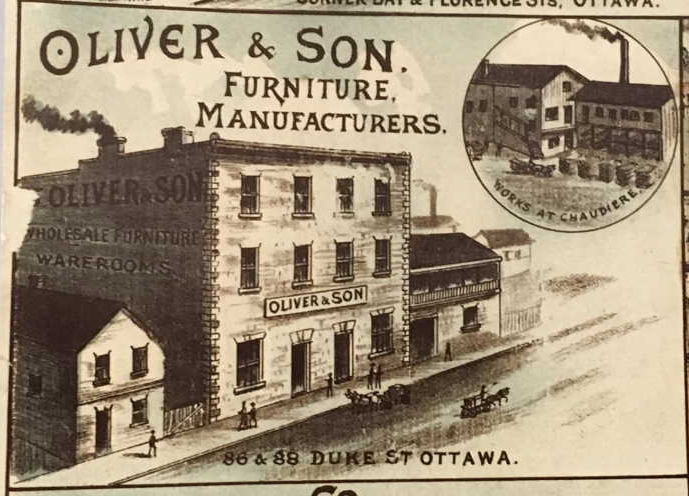

Oliver & Sons had begun as Holgate & Oliver, operating out of a leased apartment overtop a small pump factory on Victoria Island overlooking the Chaudiere in 1862. John Oliver and his partner William Holgate were experts in cabinet making and furniture building. They would see their business take off through the establishment of the Dominion government in Ottawa, and later through the supply of hotels and storekeepers with furniture as the city continued to grow.

Holgate retired in 1872, and John continued on with his son James under the name J. Oliver & Sons. The business survived a series of four fires (most of them without insurance), rebuilding each time on a larger scale, eventually relocated to Duke Street in LeBreton Flats, and becoming one of Canada’s major furniture manufacturers.

John Oliver retired in 1899, and it was his son James who spearheaded the move to Hintonburg that year. This was a huge stroke of luck for the company, as they avoided what would have been total loss in the Great Hull-Ottawa Fire in April of 1900 (though they did still have some assets in LeBreton, including 100,000 feet of lumber). However, the insurance payout from this loss allowed them to add additional modern machinery to their Hintonburg plant.

That summer, J. Oliver & Sons built a new office adjacent the factory, and in August it was announced that another three-storey structure would be built next door, to serve as a shipping centre, warehouse and finishing/painting facility. A year later a third three-storey building would be constructed alongside the CPR railway tracks which was an enlarged warehouse. The proximity to the CPR and GTR tracks allowed the company to install railway siding that came right into the property and allowed for easy shipping, a necessity with their exploding sales numbers.

More expansion and additional buildings were added through the years, which included a showroom with 12,000 feet of floor area. At its peak the firm employed more than 100 men, most of whom lived in Hintonburg. The company had sales representatives across Canada, including the Maritimes and one in Winnipeg to handle output for the Northwest.

During WWI, Oliver & Sons began producing materials for the war, including large quantities of saddle bars, hospital furniture (including folding tables and chairs that were sent to England and France), tent supplies (for six months one machine did nothing but turning out tent pegs, four thousand daily), and shell boxes (over one million produced).

In 1923, Ernest J. Oliver, the great grandson of John Oliver, became the fourth generation of his family to manage the firm.

After the war, J. Oliver & Sons began to focus more on the production of school furniture and hall seating, contracting not only locally (they furnished the new Nepean High School and Glebe Collegiate), but also with the Toronto Board of Education, as well as schools and board across Ontario. They constructed all 5,000 seats in the new Ottawa Auditorium.

The great depression of the 1930s brought about the end of the business. A bankruptcy sale was held through the A.J. Freiman store in November of 1934, with all remaining bedroom, dining room and living room sets being sold.

Bankruptcy was finalized in Feburary 1935, and ownership of the lot and buildings shifted to the banks who later sold the property to A.J. Freiman.

Over the next 12 years, the property was split in three pieces essentially. The south part of the property, where Oliver once stacked its large holdings of lumber, was sold in October 1942 to General Supply Company which built large workshops and warehouses where they built and sold large and small machinery. When General Supply moved to Moodie Drive in Bells Corners in 1974, the regional government (RMOC) moved its transportation operations division in. The RMOC demolished most of the buildings, and in 1975 built most of the current building that exists today as home of the City of Ottawa’s Traffic Operations Control Centre on Loretta.

In 1947, Freiman sold the north part, including the old Oliver Furniture buildings for $25,000 to Lyle Blackwell, who demolished the old structures and built a large “modern dry cleaning plant” for his laundry business. This building still stands today at the corner of Loretta.

One surviving building, the old three-storey building that stood alongside the railway tracks fronting Gladstone, was sold in 1947 to Cecil Leach & Co., which moved its furniture dealership from Somerset Street. This building stood until the late 1960s before being demolished, the last vestige of the J. Oliver & Son furniture business.

Sadly today there is no longer a trace of this important business that was one of Canada’s finest for the first 30 years of the 20th century. However, their impact on Hintonburg cannot be understated, and their memory lives on through the telling of their story on the pages of the Kitchissippi Times.