By Dave Allston

The waterfront along the Ottawa River in the west end of Ottawa is an ever-evolving story that continues to be written.

In early days, the river was a major transportation route for First Nations traveling to the western interior, and the Algonquin people used its banks for hunting, gathering, farming, trapping and fishing. Later, early Colonists arrived at Richmond Landing and the Honeywells near Woodroffe, leading to the development of cottage communities and eventually residential neighbourhoods.

Some readers may already be aware that the shoreline was artificially built up in the 1960s, creating an abundance of new land extending from downtown all the way to Mechanicsville. This was land for which the city and NCC had grand designs.

It all began in the late 1950s when a series of City and NCC projects all intertwined following the commencement of the NCC’s implementation of the Greber Plan. The railways, around which our neighbourhoods were initially built, were to be torn up and relocated to the east end of town. Sewers were to be installed to provide much-needed infrastructure to the expanding city. The parkway and Queensway were being planned to handle the exploding traffic problem.

Land reclamation was a popular concept in the mid-20th century, as cities sought to convert wasteland into usable space. Garbage was used to create it. Waste could be simply dumped into the water, creating new land in a prime location.

At the time, Montreal was building Notre Dame Island using the rock from the creation of the subway system. The Toronto waterfront was quickly being expanded using excavation and construction waste from subways, office towers and other large projects. Many cities throughout the U.S. were using similar landfill schemes to build up their central areas.

Between Mechanicsville and downtown Ottawa existed three significant bays: Lazy Bay just north of Laroche Park; Bayview Bay between the Lemieux Island Bridge and the now Chief William Commanda Bridge; and Nepean Bay, the north end of LeBreton Flats. Soon all three would become a part of a grand NCC plan.

Nepean Bay was the deepest bay of the three. Located in close proximity to downtown and the Chaudiere Falls, it presented the largest opportunity for development. The Federal District Commission (FDC) had been actively acquiring land along the water for planned parkways, and were particularly enthusiastic to acquire the land alongside Nepean Bay, which they did in early 1957. They immediately announced lofty but vague plans to establish large sandy beaches and recreational spaces there.

By 1959, the city garbage dumps in the east and west ends were reaching capacity. The city had spent years attempting to find other options but found none suitable within the city limits. They began to consider sites in Gloucester and Nepean, but no easy solution could be found.

In a letter to the Board of Control in February 1959, Ottawa Works Commissioner Frank Ayers suggested that a site could be established in the heart of the city — right in Nepean Bay along the Ottawa River waterfront. It would require approval from the freshly-renamed National Capital Commission. Ayers detailed a plan that required a causeway to be built to retain the garbage, which would also allow access for trucks to dump the garbage. Filling in the bay would create 50 acres of land.

The Board of Control asked Ayers to go to the NCC and pitch the proposal. The CPR tracks, roundhouse and railway infrastructure at LeBreton and Bayview were already scheduled to come down as part of the $20M National Capital Railway Relocation program.

NCC officials immediately called the garbage dump plan “quite interesting,” and noted that the Greber Plan had suggested some land reclamation in this area. The National Capital Plan had always planned for Nepean Bay to be developed for recreation. The horseshoe-shaped bay had notionally been targeted by the NCC for landscaping with trees, shrubs, flower beds, lawns, a massive sandy beach and a large playground.

As it would solve the garbage dump problem only temporarily, the NCC at the same time stated that they would not oppose the use of Green Belt lands for future garbage dumps. But that was a problem to solve at a later date.

Within a week, the NCC formally approved of the plan in principle, with one NCC executive stating that the city’s plan to fill the bay with garbage “fit very well into development plans.” The NCC had been wondering how they would create the promised beach and park, as the bottom of the bay was covered with “many feet of water-rotted sawdust” from the lumbering era.

Meanwhile, another major City project was just getting underway – tunnel drilling for the Ottawa Interceptor and Outfall Sewer project, a key piece of the $20,650,000 Ottawa Sewage Disposal Project. Millions of tons of rock were to be excavated in building the tunnels from Booth Street under Wellington past the Chateau Laurier and east through to the new sewage disposal plant being built at Green’s Creek. This provided the perfect opportunity to acquire the massive quantities of rock required to build the causeway.

The plan quickly fell into place. The Causeway would be built quickly as it was estimated the water in the Bay was only four or five feet deep. Then the water on the inland side would be pumped out, and garbage would be brought in over an expected two-year period to fill the horseshoe. A thick layer of soil would be added and then tons of sand at the water’s edge to make the beach, creating what the NCC predicted would become “one of the finest waterside parks in Eastern Ontario.”

In December of 1959, the Board of Control approved the construction of the causeway from Nepean Bay all the way west to Mechanicsville’s Lazy Bay.

The bay at Lazy Bay continues to exist today, though at a vastly reduced size. Originally, the Bay came up to Burnside Avenue and Laroche Park. In fact, Stonehurst used to continue through Burnside, running as a short lane for 40-50 feet directly into the water. More than a few stolen cars ended up in Lazy Bay via this little lane.

Until the 1960s, there were also houses on Carruthers and Hinchey north of Burnside, with a couple of the Carruthers houses sitting on Lazy Bay’s edge like a cottages.

If it sounds crazy that the City and NCC were okay with simply dropping garbage into the Ottawa River with just a small man-made rock wall to contain it, consider that at the time, raw sewage was dumped into the river from a variety of outlets all along the River. It was said that 25 million gallons of raw sewage a day poured into the river from 18 outlets along the shore and an additional 21 outlets on Victoria, Chaudiere, Albert and Amelia Islands.

In February 1961, the City heard that the Riverside Drive dump had only 14 months left until it hit capacity. The rush was on to speed up construction of the causeway, which began over the winter months of early 1962.

Around this time, the plan for long sandy beaches was discarded in favour of creating the eastern entrance to the River Parkway overtop the new causeway.

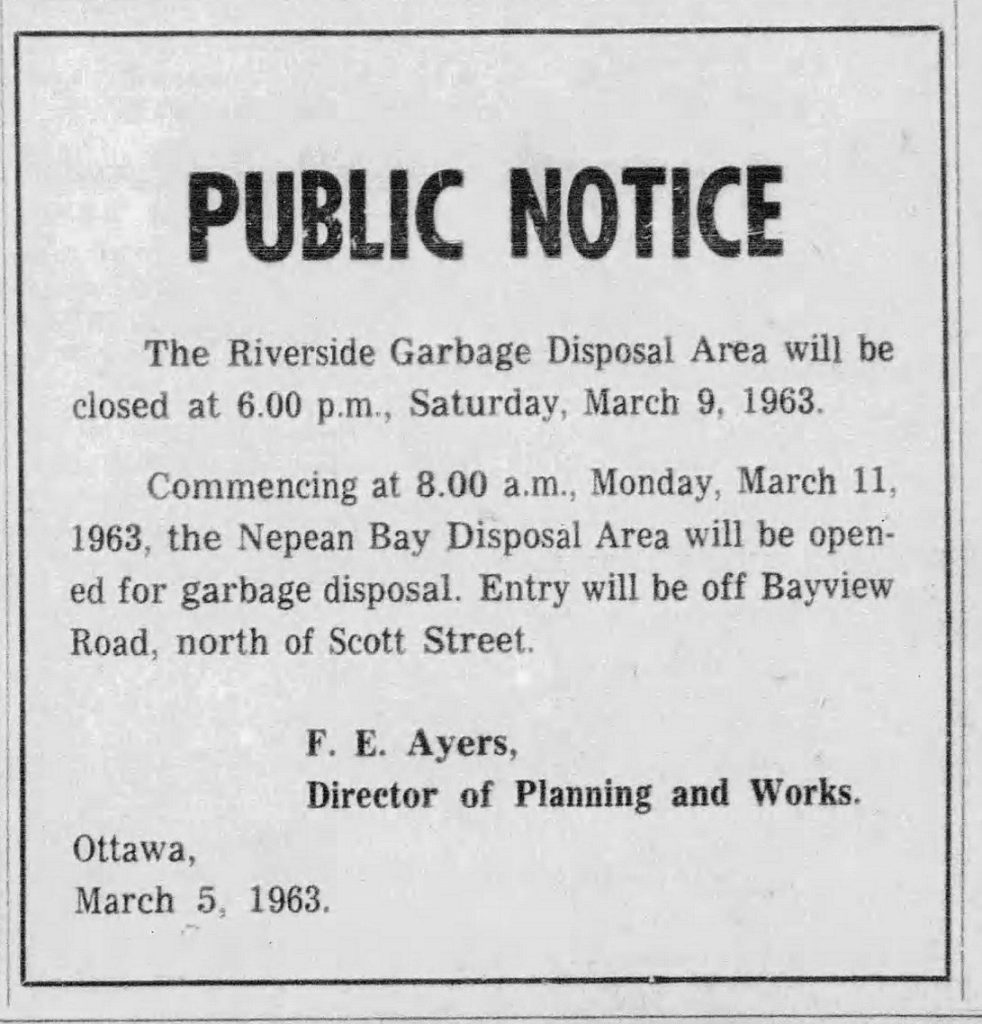

With the causeway completed, the first garbage began to be dumped in the Bay the week of Monday March 4, 1963. Meanwhile, public disposal ended at Riverside Drive dump on March 9.

The NCC also found it handy to have a dump in close proximity to the neighbourhood of housing it had begun expropriating in 1962 – LeBreton Flats. Demolition of the houses was originally slated to begin in the spring of 1964, but as families began moving out in late 1962 and early 1963, the houses left behind were targets for arsonists and squatters. Homes were vacated gradually and in no particular groupings, so inhabited houses stood side-by-side with the abandoned.

The NCC quickly began pulling down the houses, and placing them in the Bay. Many of the original LeBreton Flats houses still exist today – buried deep below the Parkway.

This hastened the filling of the dump, which hit capacity and was closed on February 1, 1964, more than a year earlier than planned. Lazy Bay and Nepean Bay were now full.

In the October issue of KT, Dave Allston will explore how the transition was made from dump to usable space.