By Dave Allston

As the Christmas season is upon us, it is timely to look back at a Kitchissippi story lost largely to time.

Today the stately home at 539 Island Park Drive acts as the Peruvian Ambassador’s residence, but in 1940, especially around Christmas, this house was the affectionate scene for a group of evacuated British school children who came to Canada as WWII intensified, with little warning, no money and no possessions. Ottawa, and particularly our west end community, adopted these “child guests,” providing a welcoming home during a terrifying time.

The home was known as Byron House, named for the private school located in the upscale London neighbourhood of Highgate Village from where the children and staff came. As the threat of bombings grew in London in 1940, a general evacuation of children was ordered.

The Canadian government extended an invitation to Britain to evacuate their children to Canada, with many residents offering up their homes. A direct cable was sent to Byron House offering accommodation for the school as a group.

Within days, the Byron House kids were on a ship to Canada, travelling as part of a convoy of evacuation ships that were under constant threat of attack from airplanes, land vessels or submarines. The 28 children were guided by the school’s headmistress Leonora Williams, who was accompanied by four staff.

The group had only £25 with them, and no further funds were allowed to be sent out of Britain, as all money was directed towards war supplies and armaments.

The group’s desperate situation only got worse in Canada. After travelling west by train towards Ottawa (where one four-year old remarked that though he loved the Canadian trains, their whistles reminded him of air raid sirens), when they finally arrived in Ottawa, they discovered that a mistake had been made. No arrangements had been set up for them. They had nowhere to go.

They were offered temporary housing at Elmwood School in Rockcliffe, which had been vacated for the summer. Other evacuated British children arriving that same week were dispersed throughout Ottawa to private homes and institutions such as Ashbury College and the Ottawa Ladies’ College. The Children’s Aid Society (CAS) organized the program, working to ensure that children were “enabled to live on the same social and economic level that they were used to at home”. Children from rural areas were in rural communities, while urban children went to families in the city. CAS sent letters and photos of the children in their new surroundings back home to worried parents.

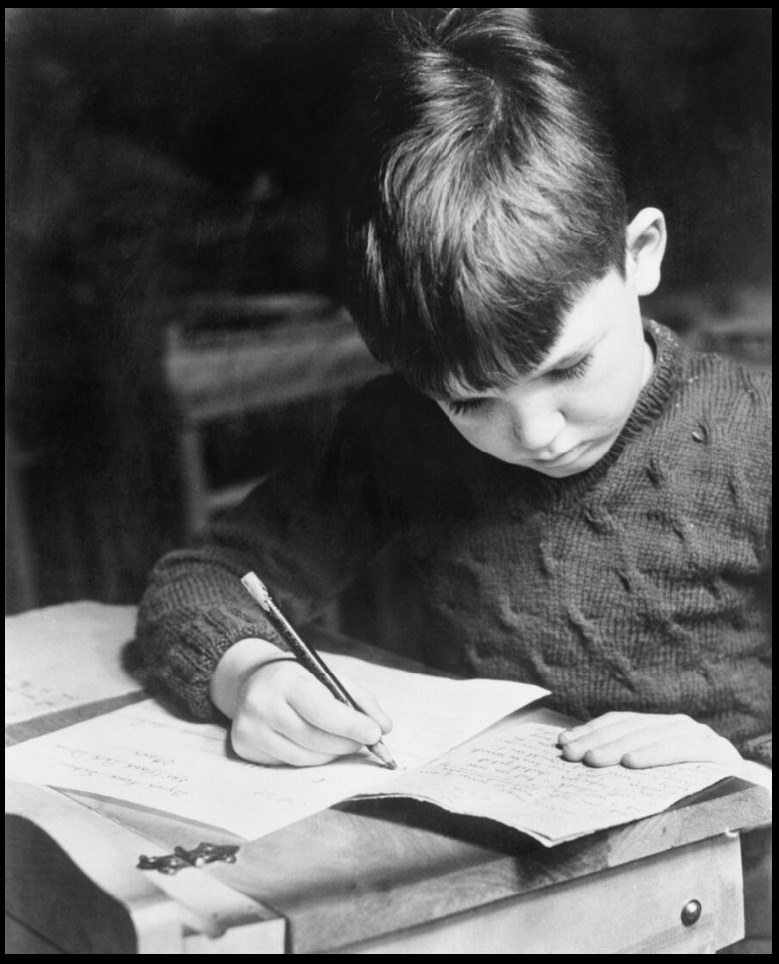

For the Byron House children, those aged eight or above were boarded out to families and attended regular schools, as it was felt they would benefit from assimilating with Canadian children. The younger children were kept together under Leonora Williams’ care.

Soon the term “evacuee” became taboo, replaced with the more thoughtful term “British child guests”.

By summer’s end, with the fall school season about to begin at Elmwood, the Byron House children needed a new home. Word got to Dr. Stafford Kirkpatrick and his wife Lina, owners of 539 Island Park Drive, which had sat vacant for nearly two years after Kirkpatrick had retired and the pair had moved to Vancouver.

When the house was constructed in 1929, not only was it one of the first homes to be built on the still relatively new Driveway, but it was also one of its grandest, built on a set of four lots of what was considered one of the most picturesque portions of the Driveway across from Hampton Park. Kirkpatrick hired the architecture firm of Noffke, Morin and Sylvester to design the home in the Tudor style. The six bedroom home cost $60,000 (equivalent to over $1M in 2023 money), with high-end finishes and an angular wing on Helena which provided accommodation for the servants, chauffeur and garage. The house set the tone for future construction on Island Park.

When Kirkpatrick attempted to sell in 1938, it would prove impossible. Advertised as “the most complete and beautiful home in Ottawa”, even at a reduced sale price of $35,000 (nearly half its construction cost), a buyer could not be found in the depressed economy. The house sat vacant through 1939 and most of 1940. It became a perfect solution for the Byron House group.

The Kirkpatricks offered the house free of charge. Nepean Township agreed to waive all property taxes, and the NCC and Hampton Park Village Community Association consented to the plan.

As word spread, many charitable organizations and private individuals in the community stepped forward with donations of supplies needed to get the school up and running. Retailer Lawrence Freiman rounded up newly manufactured furniture for the new home.

On Saturday Aug. 31, 1940, the 16 children (eight boys and eight girls) made the move to Island Park Drive.

All of the rooms found new functions. Even the former two-car garage became a woodworking room, where the children could learn to use donated tools. The large drawing room was converted into a classroom for the younger children, the former living room a classroom for the older group.

“At one time it was probably a luxuriously furnished room with deep piled Persian rugs on the floors, heavy draperies at the windows and oil paintings on the walls. Now the floor is bare, the windows undraped, the furniture consists of 10 small desks, and the paintings, childish scenes of autumn trees, unstreamlined automobiles and almost eatable looking pears, apples and grapes. But the room has lost none of its beauty, for now it is filled with life, young eager life”, wrote the Citizen.

The Ottawa Women’s Canadian Club was most generous in regularly supporting the school. In October, they held a “pound party” at the Chateau Laurier, attended by Princess Juliana of the Netherlands where over 600 members contributed jams, jellies, pickles, and dry groceries to help stock Byron House’s pantry.

The Ottawa Protestant Children’s Hospital established a special clinic for British Child Guests, with volunteers from the Red Cross Society driving the children to appointments.

The local community gave endlessly. Individual residents gave donations and sponsored children. The firemen of Station No. 11 on Parkdale Avenue made items for the home, including wooden shoe racks and easels for art classes. The newly-formed Hampton Park War Service Committee, established to make clothing items for soldiers, contributed 17 pairs of mittens in 1941. Soon many of the girls (and some boys) from Byron House joined the Committee and helped knit sweaters to send overseas.

The staff included three teachers from England (Leonora Williams, Mary Mason, Marjorie Clarke), a fourth teacher from Boston, Massachusetts (Anne Sanborn), a cook (Mrs. Robert Brown, a Westboro widow), and two maids (including Westboro’s Jean Percival). Leonora worked tirelessly to ensure the success of the school. “Initiative, courage and good British ‘guts’ are the qualities Ottawa has discovered in Leonora Margaret Williams”, stated the Citizen that fall.

The children kept to a tight schedule, which included two neighbourhood walks each day, and lights out by 7:30 each night.

One of the first projects completed by the children was a miniature recreation of Island Park Drive, “Representing hours of fun and a great deal of initiative, the district on either side of Byron House School has been faithfully constructed, paper house by paper house. Blocks are marked out, paper sign posts with the names of streets have been erected, and trees and shrubs have been gaily strewn about,” reported the Journal.

That fall the children were introduced to jack o’ lanterns for the first time. They took in an Ottawa-Hamilton football game at Lansdowne Park, and celebrated Armistice Day. Neighbourhood volunteers would also take the children out on sight-seeing trips around the city on weekends.

Christmas was a particularly celebratory time. A large Christmas party was held for Ottawa’s 150 British child guests at the Chateau Laurier put on by a group of British-born Ottawa residents. The children were given gifts and cake, and watched a Charlie Chaplin impersonator, a ventriloquist, and film clips and cartoons. The Elmwood Old Girls’ Association also put on a Christmas party at Byron House, where Santa brought stockings containing gifts, and movies were shown. On Christmas Day itself, the Ottawa-based Marionette Theatre put on a performance of Jack and the Beanstalk.

Over the next three years, Byron House continued to be a hub of activity. A Girl Guides Brownie Pack (40th Pack) was established in 1941. Later a nursery was opened in the playroom, enabling mothers of small children in the area to attend meetings of the Hampton Park War Service Group.

Eventually, one by one, the British child guests in Canada began to return home. Byron House on Island Park Drive was closed by late 1944.

Sadly, Dr. Kirkpatrick passed away in 1943, and in June of 1945, his estate sold 539 Island Park Drive to the Government of Peru for use of the first Peruvian Ambassador to Canada. It remains the Ambassador’s residence today.

The houses of Island Park Drive each have a unique story to tell, and the Kirkpatrick House may have one of the most laudable. Not only is it one of Kitchissippi’s most architecturally magnificent homes, it represents a key milestone in the development of Island Park Drive as a destination for embassies. It symbolizes the generous legacy of Dr. Kirkpatrick and the significant role Canada played during WWII on the world’s stage.