For decades during the earliest days of Kitchissippi, there was a small but significant geographic feature that created constant problems for residents. It slowed development, caused major political headaches, ruined new infrastructure, and even led to severe illness and death. Cave Creek was the scourge of old Kitchissippi.

In the late 19th century, Cave Creek still ran through what was essentially wilderness. Though Hintonburg and Westboro had begun their slow growth, 95% of the ward was still open farmland, orchards, thick woods, and a swampy creek. Farm and forest were easy for residents to tackle, creek water, not so much.

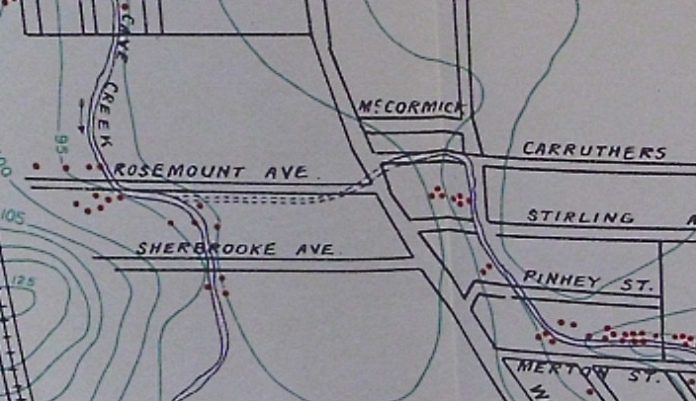

The earliest mentions of Cave Creek appear in 1887, when the Ottawa Field Naturalists Club (today still a popular natural history group) took trips out to this area to explore this fascinating and “remarkable” creek. Early attempts to map its route show it started in multiple locations south of Carling, as far west as Maitland, and as far east as Fisher. Its primary route was from where the Queensway crosses over Island Park Drive, east through the Elmdale area, and then north by Fisher Park School. It then ran eastwards to Rosemount, south to Carruthers, east to Merton, and then north through Laroche Park, where it emptied into the Ottawa River. There were also many branches running off this primary route. Any residents who now live in the vicinity of its path, or directly on it, have undoubtedly suffered its effects.

The most interesting section of Cave Creek was the area around Rosemount Avenue, halfway between Gladstone and Wellington, where it ran underground into a series of caves, and then came back to the surface near the south end of Carruthers. In fact, Carruthers was originally called “Cave Street” for this very reason. Hintonburg had many caves running underneath and many likely still exist.

Trouble would arrive each spring when all of the farms south of Carling (including the Experimental Farm) would drain off their land. They were encouraged and permitted to do so through a series of ditches but property owners in burgeoning Hintonburg were left to deal with the consequences.

Land was expropriated to extend Armstrong west of Merton specifically for drainage. Ditches were constructed, culvert crossings made, and the creek bed itself was deepened. In 1898, the Ottawa Land Association also constructed cedar wood-encased drains down Holland to the Ottawa River, which created a second entry point to the river but efforts proved futile.

Making things worse was that this open creek – running almost year-round through Hintonburg – became the community’s sewer. Underground sewers were difficult to construct in this rocky neighbourhood and the independent village could not afford to build them. When Ottawa was constructing new sewers at Preston Street, Hintonburg asked if the capability to connect up to them in the future could be built in, but was refused. So Cave Creek was used as the sewer, and those who lived on its banks took advantage: constructing outhouses, stables, pigpens, and even back rooms of their houses, directly overtop the creek. Septic tank runoff from the Lady Grey Hospital (now the Royal) on Carling ran into the creek, as did animal waste from farms.

Removing garbage and loose stones to allow for the creek’s flow was crucial, but by 1906 Hintonburg was incapable of maintaining the creek. There were reports of “cesspools in the streets” throughout the village.

In December 1907, Hintonburg became part of Ottawa, chiefly on the promise that its sewage issues would be resolved. Ottawa refused the outlet to their sewage systems prior to annexation, and afterwards held off on construction for several years due to politics and legal technicalities.

The situation exploded in February 1911 when a typhoid fever epidemic hit Ottawa resulting in 1,196 cases and 87 deaths. The province investigated and deemed Cave Creek to be the cause. Though the main Ottawa drinking water intake valve was located past Lemieux Island, in periods when the river’s water levels were low, or when additional water was required for fighting fire, the secondary intake valve at Pier 1 was opened. Pier 1 was located immediately downstream from the Cave Creek entry. This meant that people living in Ottawa drank Hintonburg and Mechanicsville’s untreated sewage on numerous occasions.

The Provincial Health Inspector noted: “The sanitary condition is one which would hardly be tolerated in any hamlet in the province of Ontario, much less in the Capital city of the Dominion of Canada.”

Ottawa immediately began treating its water with hypochlorite of lime. It also moved Hintonburg’s outhouses and established some public health initiatives, including sewer construction in Hintonburg soon afterwards. However, there were still issues with contamination to the city’s water supply. Health concerns were generally ignored and covered up. Old, leaky and unreliable pipes remained, new sewers were delayed, and an expensive septic tank at Laroche Park was constructed but never used. Typhoid’s return to Ottawa in June 1912 resulted in 1,400 new cases and 98 fatalities. Unbelievably, it would take 19 more years until the problem was finally solved with the opening of the Lemieux Island filtration plant.

While this resolved the issues east of Parkdale, the west still suffered. When the ice jams near Carling broke in the spring, the water would pour over the land, flooding the area. In the fields west of Holland (in what is now Wellington Village and Hampton Park) the water would be seven feet deep in most places, and up to 15 feet in the lowest spots.

Compounding the issue was that the Ottawa Land Association began selling their Wellington Village lots in 1919 and house construction began. Each spring, the houses would become marooned and residents were forced to move their furniture upstairs. The City of Ottawa expropriated 15-foot wide strips of land behind several streets to construct ditches and drains, but it was insufficient. An earthwork dam was proposed in the Elmdale area, but rejected. Many houses built in the vicinity of the lowest point (such as those on Huron Avenue) were constructed on foundations six feet off the ground for this reason.

Engineers proposed solutions as early as 1922, but it took five years of political wrangling over cost sharing before the project could finally get underway. Eventually, the Cave Creek Collector was built: a 72-inch reinforced concrete pipe through the neighbourhood, primarily under Harmer and Huron (hence their exceptional width). The final bill for the work was split three ways: property owners west of Parkdale paid 18%, Nepean 10%, and Ottawa 72%. The system was completed in December of 1927, and still exists today.

Dave Allston is a local history buff who researches and writes house histories and publishes a blog called The Kitchissippi Museum. His family has lived in Kitchissippi for six generations. Do you have photos or stories to share about Cave Creek? We’d love to hear them! Send your email to stories@kitchissippi.com.

* The image at the top of this page is part of a fire insurance plan from 1898 and shows the route of Cave Creek along Armstrong, then north up Merton.