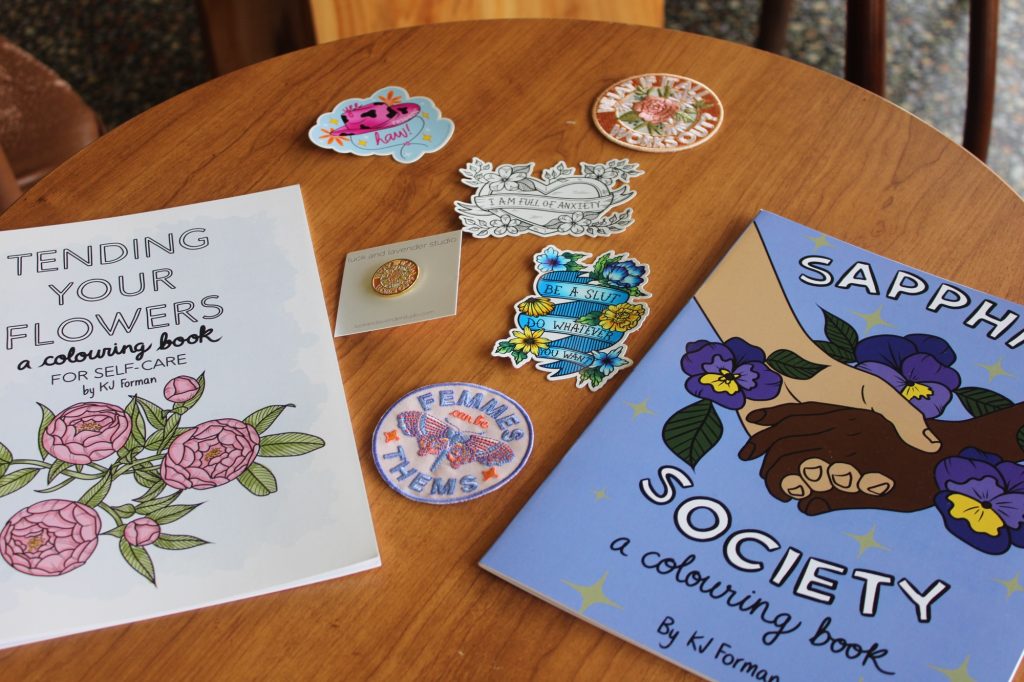

KJ Forman’s “soft art with a hard edge” includes a punchy feminist phrase with flower and skull designs to represent beauty and hardship.

Through their ups and downs, art has been the means through which Forman has explored their non-binary identity and empowered many.

In 2018, Forman debuted their art at their first market of many, the Feminist Fair.

“I remember there being a lot of queer people and I remember feeling that I belonged there,” Forman recalled. “It was essentially all feminist makers sharing their art. I had a table there and didn’t know what to expect but it was the best day ever. I had an amazing time and I remember feeling at the moment: this is what I want to do.”

Now six years later, Forman says they would have never thought a blossoming career as an artist was possible.

They first sold prints for their original business, Lucky Little Queer, but quickly began experimenting with other mediums. Forman creates designs digitally to feature on t-shirts, stickers, totes, pins and patches, but they have also worked with fibre arts, swimsuits, and painting over records.

“I like to do one-off illustrations that are easy to put on stickers and things that people can share whenever they want. Art that people can take with them is something I really like,” they said. Forman’s phrases and doodle ideas accompany spur-of-the-moment thoughts, emotions and memories.

Through their first five years as Lucky Little Queer and their rebranding to Luck and Lavender for the last two, Forman has also made strides to reclaim their identity and embrace joy from their queerness.

The expectation that being non-binary means a masculine or androgynous appearance has always felt uncomfortable for the artist who prefers presenting more femme. During the pandemic, they discovered that they felt more themselves when they stopped conforming to the traditional ideals.

This included growing their hair out and styling it differently, wearing makeup the way they liked, and wearing outfits they found comfortable.

“I’m read as quite femme but that doesn’t make me any less non-binary than other people.”

Wellington West resident Darby Babin, who is also non-binary and Forman’s longtime friend, echoed these challenges.

“The short hair and all the things we feel we have to be when we were newly out as queer – it can be hard to claim any femininity you may like when you feel you have to perform. They’ve rebuked that idea that all non-binary people have to have the same androgynousness,” Babin said.

To combat these stereotypes, Forman designed a piece that said ‘Femmes can be thems.’ Earlier this year at Toronto Pride, they were approached by another femme-presenting non-binary person who had similar experiences.

Many non-binary and transgender individuals are accustomed to others being unable to see them the way they see themselves. Babin added that many feel like they owe parts of themselves to others.

“I don’t know if people notice this about the non-binary people in their lives but we get misgendered 1000 times a day every day because people have a very limited view of what gender identity can be,” Forman says.

It’s easier to accept this reality rather than correct others. Femme-presenting people, including Forman, have been discouraged from sharing their non-binary identity as well because their queerness is taken less seriously than masculine-presenting people. This was a common barrier they experienced while trying to make a name for themselves earlier in their career.

Alongside the Luck and Lavender collection of punchy feminist phrases, Forman has created mental health designs. These are inspired by their own experiences but have resonated with the artist’s growing audience.

“It’s something I do for myself, but I find it opens up a larger conversation about mental health which isn’t something I intended to do, but it’s really beautiful to actually see,” they said, adding that people often see themselves in Forman’s work.

While waiting for a doctor’s appointment, Forman wrote ‘I am full of anxiety’ inside a banner on a tattoo-style heart. Now one of their most popular designs, Forman noticed post-COVID an increased demand for their mental health pieces.

‘What if it all works out,’ another popular phrase, was coined in a therapy session years ago to rebut their catastrophic thoughts and remind themselves that the good also exists.

Today, Forman wants to maintain their peace. They attend markets most weeks and are deeply connected with the community.

“It’s nice when I enter queer spaces and oftentimes I’ll hear people say they’ve seen my art before or they have a print of mine hanging on their wall, and I don’t even know how to describe how good that feels,” says Forman. “It feels very important and surreal to make an impact in my city because I really love Ottawa.”

“They never take it for granted at all,” Babin added. “It means so much to them to help others feel seen. They never take a second of it for granted and they always give back as much as they can.”