By Dave Allston

This year marks an incredible milestone in the history of Mechanicsville: 150 years! Yes, it was in 1872 that two Bytown entrepreneurial industrialists laid out a subdivision on the outskirts of town, though Mechanicsville was actually secondary to their main plans for the property.

Just a tiny neighbourhood four streets wide and three blocks deep, Mechanicsville packs an incredible amount of history into every square inch. The village built up quickly, and for most of its 150 years remained the same: a veritable time capsule of a 19th century working-class neighbourhood. However, in recent years, the character of Mechanicsville has changed rapidly. Original houses are counting fewer and fewer, and the neighbourhood’s colourful history is disappearing bit by bit.

To tell the full story of the neighbourhood could not possibly be done in one column (I am working on a long-overdue book!). So for this article, I thought it would be interesting to tell of the birth of Mechanicsville: how it came about, who was behind it and the meaning behind the name.

The story of Mechanicsville begins in 1870, when Alanson Hovey Baldwin and Thomas McDonough Blasdell acquired all of the land north of Scott Street—from about the middle of Tunney’s Pasture, east to the middle of Laroche Park. These were Nepean Township lots 35 and 36 in concession A, and were part of a large estate of land owned by the heirs of Nicholas Sparks, who had operated a mill at the river’s edge (at about where Hinchey would hit the water if it continued in a straight line).

Baldwin had come to Bytown and opened a saw mill at the Chaudiere in 1852, one of the “American Invaders” to the area in the 1850s. By 1870, he was running two mills, a blacksmith shop and a shipyard for building barges on Victoria Island, employing 400 men.

Blasdell meanwhile had come to Bytown as a teen in the 1820s. His family operated a foundry and ironworks at the Chaudiere, and, eventually, Blasdell operated his own, known as the “City Foundry and Machine Shop,” and was well-known for his axes. By 1870, he was out of the foundry business, working as an independent engineer and machinist.

Having worked their entire careers around the Chaudiere, it was the potential of the Ottawa River upstream that interested them greatly. Known as the “Little Chaudiere,” by acquiring the future Mechanicsville land, it also gave them what they wanted most: the water rights to the adjoining river.

The area where Sparks’ mill had existed in the 1850s and 1860s was known as “Bulkhead Point,” and by 1870 was a series of ruins and old decaying buildings, one or two of the old millworker houses still habitable. This location would later be known as “The Beaver” (at the point) and “High Rock” (along the shore a little south) by locals.

At the time, Mechanicsville was just wild, overgrown cedar brush and swamp land, which was known as good hunting grounds for partridge. Years earlier, the original Richmond Road passed through the property, which likely had its beginnings as an Indigenous path.

Setting the stage for the new subdivision was the arrival of the Canada Central Railway in 1870, which ran trains along what is now the Transitway/LRT line, from LeBreton Flats to Carleton Place and beyond. Rail operations were booming at LeBreton Flats, and there were plans to soon see expanded railyards and more mill operations to the west, in the Bayview vicinity.

Baldwin and Blasdell, however, were focused on the water rights. They wanted to harness the water power upstream from the industry at the Chaudiere, and had plans for what were known as the Little Chaudiere Falls and Rapids, as well as the land alongside.

By 1872, the pair’s plans had been slowed by court battles over the recent damming of the Ottawa River at the Chaudiere by mill-owners, the City, and the Canada Central Railway. Baldwin and Blasdell argued that the huge dams, piers and booms installed in the river were causing water to back up significantly, causing flooding of their land, but, more importantly, diminishing the water power at the Little Chaudiere.

The legal battles continued into 1873 and meanwhile, the pair decided, perhaps for financial reasons, to create a new neighbourhood on their idle land.

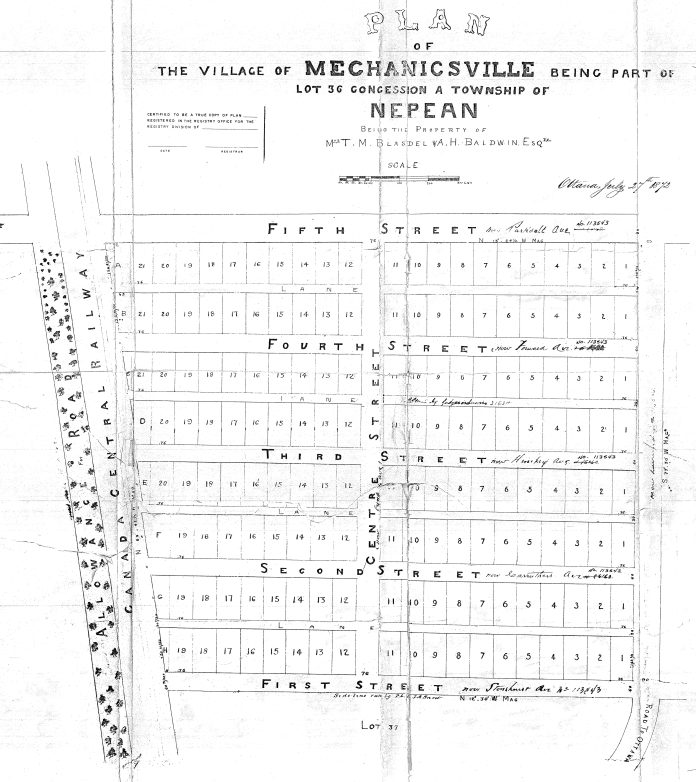

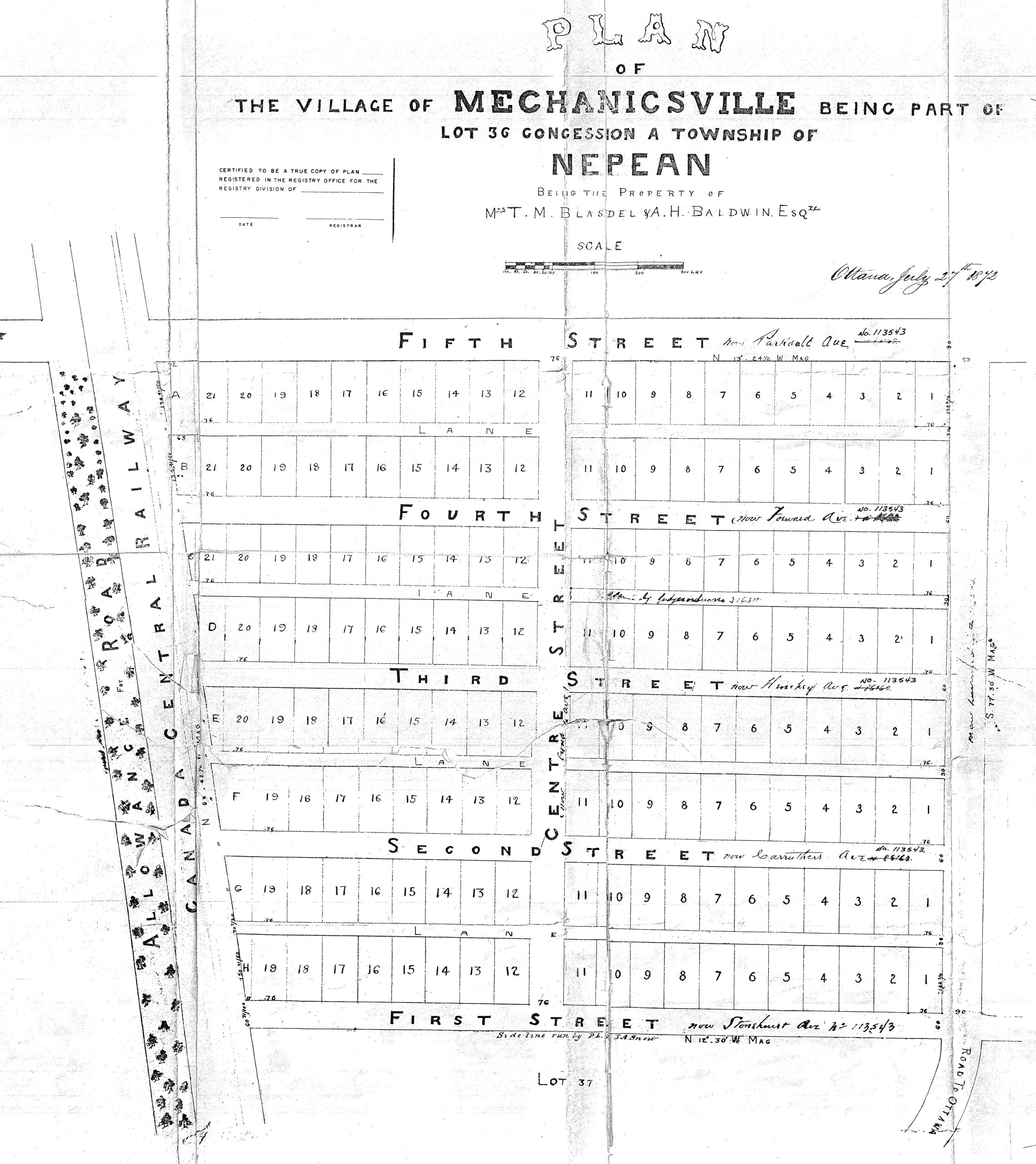

Mechanicsville was laid out on July 27, 1872, and the initial plan included just the area south of Burnside Avenue. The streets had numbered names (Stonehurst Avenue was “First Street”), and the 168 lots were laid out with roughly equal dimensions of about 50 by 98 feet. Behind each block was a 20’ lane. Mechanicsville would be expanded by an additional 44 lots just a few months later in November 1872, with a plan that laid out the section north of Burnside.

The name “Mechanicsville” was selected by Baldwin and Blasdell. In 2022, this conjures up images of a car repairman, but in the 19th century, a “mechanic” was simply a manual labourer. Baldwin and Blasdell envisioned the community as a home for working-class folk, who would be working locally in the prospering industry. They likely saw it as a community for the workers at their planned mill operations nearby.

One notable part of their plan was that streets were laid out just 40’ wide (including sidewalks). This created the narrow roadways that we still have today. No one would have anticipated the logistics of automobiles and parking, which was more than 30 years away.

The earliest lot buyers were largely mill and rail labourers, who had little or no savings. In many cases they were sold their lots, and even the materials to build their houses, on credit from Baldwin and Blasdell. As such, many earlier buyers could only afford to purchase a half-lot, and build on just 25’ of land (hence why many Mechanicsville lots today are so narrow).

As there were no building restrictions or setback requirements in 1872, to maximize their limited space, early homebuilders didn’t worry about front lawns, or front verandas, and simply built their homes at the very front of the property line. 150 years later, Mechanicsville’s narrow streets and front doors opening onto the sidewalk are character features that set it apart from almost all other neighbourhoods in Ottawa.

Many of Mechanicsville’s first houses were basically wood-frame boxes, with a single room downstairs that was a combined kitchen, living room and bedroom, with one room upstairs that acted as a bedroom for most of the family (whose average numbers typically ranged from five to 10 or more in a house). The houses were not built to hold warmth. A stove heated the home in the winter, and renovations were required when electricity, water and sewage finally did arrive. For all of these reasons, Mechanicsville had the city’s highest infant mortality rates for many years.

The construction of houses was often gradual, progressing paycheque by paycheque. A second floor was added as it could be afforded. Additions off the back, or a summer kitchen, came later. The few houses that did have brick added did so many years after construction.

Records indicate that within the first nine months of Mechanicsville’s existence, 102 lots had been sold, and the first 12 houses were built. Of those 12 houses, only two remain standing: 76 Stonehurst, built by 28-year-old labourer James Cook; and 85 Carruthers, built by 30-year-old stonemason F.X. Sauve (my great-great-great grandfather).

The first shop in Mechanicsville was a small grocery store to serve the growing neighbourhood, operated out of the home of William Gilbault at 28 Burnside (demolished in the 1990s). Gilbault was a horse teamster, and it is likely the shopkeeping duties fell to his wife.

Baldwin and Blasdell never achieved their planned water and mill operations. Canada suffered through a long and unrelenting economic depression that began in 1873, and, after borrowing $7,000 against the land in 1874, the pair began selling shares in their property to various lumber merchants. But by 1880, all the surrounding land and unsold Mechanicsville lots were surrendered to the mortgage holder.

Meanwhile, despite the depression, Mechanicsville would continue to grow steadily. The neighbourhood became predominantly francophone, with more than 80 per cent of residents in the late 1800s and early 1900s being French. Mechanicsville Separate School was built at 159 Forward in 1886 to accommodate the growing number of children. However, until the first St. Francois D’Assise Church was built on Wellington in 1890, Catholics had to walk to a small chapel in LeBreton Flats for services.

Annexation to Ottawa was seriously discussed as early as the mid-1880s, but it would not be until 1911 that Mechanicsville joined Ottawa, largely out of need for fire and sewer services that Nepean Township could not provide.

It would be quite an experience to jump in a time machine and visit Mechanicsville of the 19th century. Thankfully, we still have some traces of its early days, but they are sadly dwindling. The memories and stories will live on, through the proud and loyal residents and descendants of Ottawa’s most character (and history)-filled neighbourhood!